じゆうな じ

じゆうな じ

タイポグラフィは自由であるべきだ、という話。

今、デジタルで生成された均整のとれた文字があふれている。 その完璧さは便利であると同時に、どこか無機質で息苦しい。 そもそも字には書く人のクセが表れ、人間らしい温かみがあった。 そして印刷では文字はデザインされ、独特な魅力を纏っていた。 掠れや滲み、途切れといった偶然さえも美となる「自由な字=じゆうな じ」づくりの名手である浅葉克己さんを訪ねた。 トンパ文字、書、タイポグラフィを巡る文字の冒険家の軌跡を辿る今号の特集ページ。 この号を読んでタイポグラフィの楽しさを知ってもらえると嬉しいです。

じゆうな じ

Feature | 2025.10.24

タイポグラフィは自由であるべきだ、という話。

今、デジタルで生成された均整のとれた文字があふれている。

その完璧さは便利であると同時に、どこか無機質で息苦しい。

そもそも字には書く人のクセが表れ、人間らしい温かみがあった。

そして印刷では文字はデザインされ、独特な魅力を纏っていた。

掠れや滲み、途切れといった偶然さえも美となる「自由な字=じゆうな じ」づくりの名手である浅葉克己さんを訪ねた。

トンパ文字、書、タイポグラフィを巡る文字の冒険家の軌跡を辿る今号の特集ページ。

この号を読んでタイポグラフィの楽しさを知ってもらえると嬉しいです。

On Why Typography Is Meant to Be Free.

In a world filled with perfectly symmetrical,

digitally generated fonts, their convenience is often accompanied by a certain inorganic, suffocating uniformity.

Originally, writing revealed the unique character of the person who created it, imbuing it with a human warmth.

In printing,

characters were designed and enveloped in a unique charm,

where even accidents like blurring, bleeding,

or broken lines became beautiful.

We visited Katsumi Asaba,

a master of creating “Typography Unbound”.

The feature story in this issue traces the journey of this “adventurer of characters,”

exploring his work in Dongba script, calligraphy, and typography.

We hope that by reading this issue,

you’ll discover the joy of typography.

かつて、文字は本やポスターなどの紙の上で重要な役割を果たし、

デザイナーは工夫を重ね、ときには写植文字に手を入れながら表現した。

デジタル化が進んだ現在、文字は機能性が優先されるようになったが、それでも紙に印刷されたタイポグラフィが人の心に響く力を失ったわけではない。

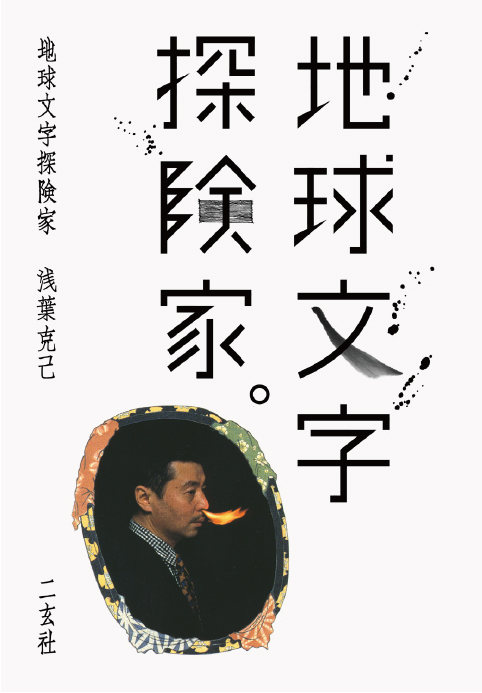

そんなタイポグラフィの魅力を探るために、「地球文字探検家」を名乗り、世界中で文字を探し続けてきた浅葉克己さんにインタビュー。

文字を自由にデザインする、その楽しさに触れてみた。

Once, letters held court upon paper—books and posters alike—

and designers, through craft and effort, even refined phototype characters by hand.

In today’s digital age, functionality reigns supreme,

but typography in print has not lost its ability to move us.

To explore that allure, I spoke with Katsumi Asaba, a self-styled ‘global script explorer’

who has sought letterforms the world over.

I experienced the joy of designing letters with true freedom.

印刷などで使われる文字をデザインするタイポグラフィは、書籍やポスター、雑誌といった紙媒体で中心的な役割を担っていた。言葉にあるメッセージをより鮮明に、美しく、見る人に伝えるためにつくられる文字。それをデザイン(タイポグラフィ)することはグラフィックデザイナーの腕の見せ所だった。

良質なタイポグラフィのために、デザイナーは筆画(線や点)や字形を吟味し、ときには手を入れ、ミリ単位での文字間の調整に神経を削り、紙の質感やインキの滲みにまでこだわって文字を創作した。

ところが今では、インターネットやデジタルメディアが主流となり、文字の役割も大きく変化した。無数のデバイスやスクリーンで表示されることを前提に、文字は “美しさ” ではなく “流動する情報” を支えるインフラとなり、可読性・データとして容量の軽量化・機種による再現性への対応といった機能性が重視されるようになった。Webフォントの普及により、デザイナーの選択肢が広がり、個性ある書体を戦略的に用いることが可能にはなっているが、印刷されたタイポグラフィにあった味わいや質感といった情感は伝わりにくい。

歴史的に、文字は常にメディアの変遷とともに進化してきた。活字が鉛からデジタルデータになったように、今のデバイスフォントやWebフォントも過渡期にすぎないのかもしれない。そうして時代は変化していこうとも、かつて紙の上でさまざまな表情を見せていたタイポグラフィは今でも、私たちの心を揺り動かす存在であり続けている。

字が自由だった頃があった。グラフィックデザイナーたちが競って、オリジナルの文字を創っていた。そんな時代を牽引していたのがアートディレクターの浅葉克己。「地球文字探検家」を自称し、世界各地で文字を探究することで得た知見を日本のタイポグラフィへとフィードバックする。そんな浅葉克己の旅を辿ってみれば、自由な字の素晴らしさと可能性が見えてきた。

Typography, the design of characters for print media like books and posters, was once a central role for graphic designers. They meticulously crafted type, paying attention to every detail—from strokes and spacing to the texture of the paper and ink bleed—to convey a message with clarity and beauty.

Now, with the rise of the internet and digital media, the role of typography has shifted. Instead of focusing on “beauty,” characters have become infrastructure for “fluid information,” prioritizing functionality like readability, light data size, and cross-platform compatibility.

While web fonts offer more options, the emotional weight and texture of printed typography are often lost.

Historically, type has always evolved with media, and today’s digital fonts may simply be a transitional phase. Yet, the expressive typography that once graced the pages of print continues to move us.

Katsumi Asaba, a self-proclaimed “adventurer of characters,” was a leading art director in an era where designers competed to create original fonts. By exploring his journey, we can see the wonderful possibilities and freedom of type.

浅葉克己が追い求めた文字の力。

Feature | 2025.10.24

トンパ文字との出会いが拓いたタイポグラフィの新たな可能性。

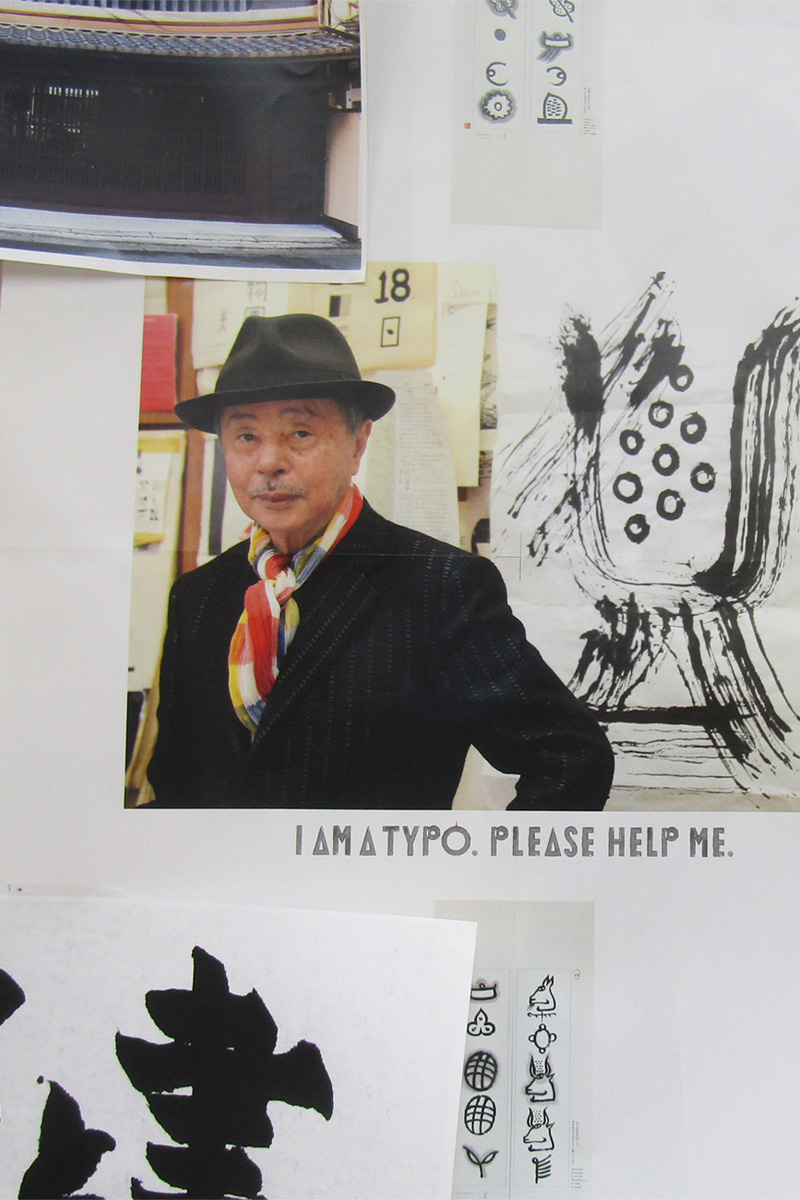

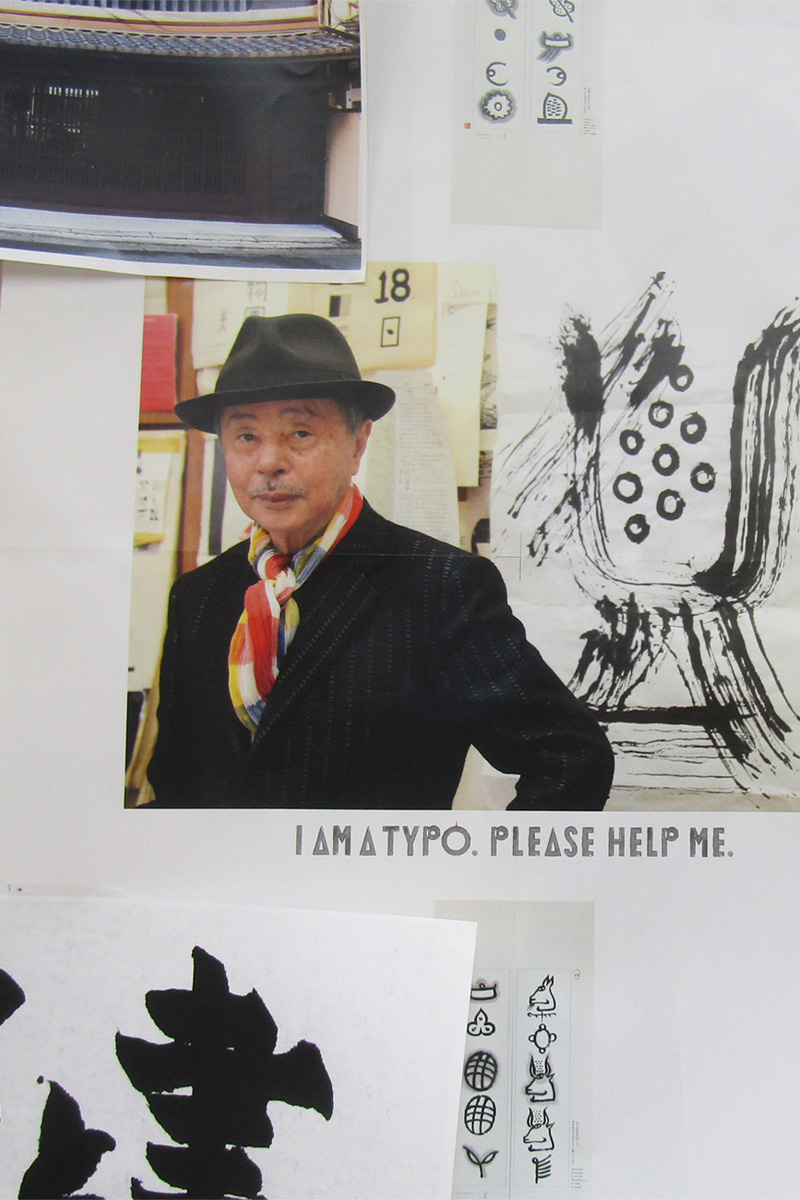

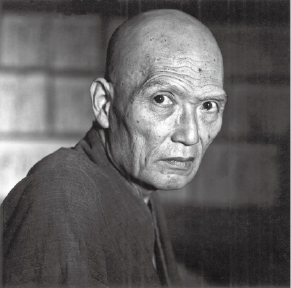

《アートディレクター》

浅葉克己 Katsumi Asaba

1940年神奈川県生まれ。

桑沢デザイン研究所、ライトパブリシティを経て、75年浅葉克己デザイン室を設立。

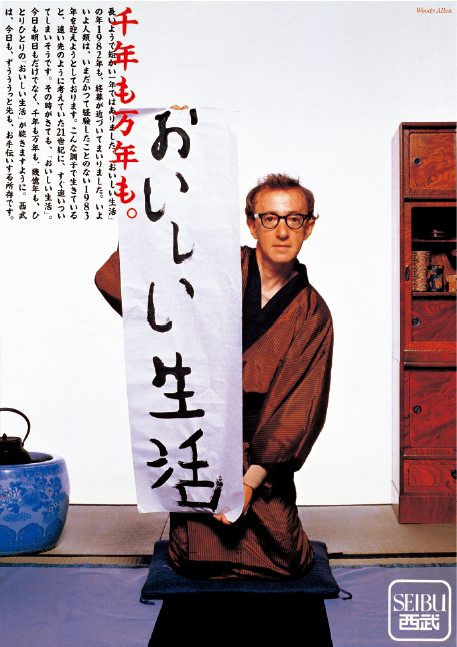

代表作に、サントリー「夢街道」、

西武百貨店「おいしい生活」、武田薬品「アリナミンA」、三宅一生のロゴマーク関連など。

日本アカデミー賞、東京ADC最高賞、紫綬褒章、旭日小綬章、亀倉雄策賞など受賞多数。

東京ADC委員、東京TDC理事長、JAGDA理事、

桑沢デザイン研究所10代目所長、東京造形大学客員教授。

京都精華大学客員教授。青森大学客員教授。卓球六段。

1970年代〜1980年代、それは日本のグラフィックデザイン隆盛の時代。亀倉雄策や田中一光、永井一正といったグラフィックデザイナーの巨匠たちが築いた土台を受け継ぎ、さらなる可能性を探り、グラフィックデザインをアートの領域にまで広げたクリエイターが活躍していた頃。そんななかでも飛びきり鋭い感性でデザイン界をリードしていたアートディレクターが浅葉克己さん。

浅葉さんは広告などのアートディレクションで活躍する一方、“地球文字探検家” として世界中の文字を探し歩き、観察し、収集してきた。「文字は深い。その探究は一生かけても終わらない」と語っていた浅葉さんにとって、文字は単なる記号ではなく、人間の文化や感性そのものを映しだす存在だったのかもしれない。

浅葉さんのタイポグラフィへの関心は国境を越えて広がっていく。西欧にとどまらずアジア、アフリカ、さらには少数民族の文字にまで目を向けた。文字はどこで生まれ、どのように人々の生活のなかで生きてきたのか。そんな探究心が浅葉さんの好奇心を刺激し、行動に駆り立てていた。

そうした旅の途上で、浅葉さんは中国・雲南省の麗江に伝わる「トンパ文字」と出会う。トンパ文字とはナシ族が用いてきた象形文字で、アルファベットや漢字のように抽象化の進んだ文字とは異なり、描かれた姿がそのまま意味に直結する。

山の形は山を表し、人の姿は人を示すといった、現存する数少ない象形文字体系とされる。絵に近い形を持ちながら、祈りや物語を記録する機能を果たすトンパ文字に、浅葉さんは強烈なインパクトを受けた。

デザインの現場では、文字は読みやすさやコミュニケーションの効率といった面から善し悪しが決められる。しかしトンパ文字は、必ずしも効率的ではない。むしろ、祈りや物語を伝えるために、象徴的であり、詩的であり、そして不完全さをも含み込む。その姿に浅葉さんは、文字が人間の営みのひとつであることを改めて実感したのだろう。

浅葉さんは現地で、ナシ族の教典を見てトンパ文字の生きてきた時間の流れを知りたいと思った。しかし教典は、日本には一冊も存在しないことを知る。そこで、現地で街の骨董屋に行き、有り金をはたいて手に入れたという。

この出来事は、浅葉さんが文字を “資料” ではなく “生きた存在” として感じたことを物語っている。現地で教典を手にし、ナシ語を聞き、祭司が語る儀式に触れ、文字が使われてきた生活の場を見たことで、抽象だけではない文字の力を改めて思い知った。そして、自身の作品や表現の中にも、こういった “文字” のあり方を取り込もうと決意する。

The power of letters as pursued by Katsumi Asaba.

How an encounter with the Dongba script opened up

new horizons in typography.

Katsumi Asaba was a leading art director during the golden age of Japanese graphic design (1970s–1980s), known for his exceptionally keen sensibility. Alongside his advertising career, he embraced the role of “planet-roaming character adventurer,” traveling the world to observe and collect scripts. For Asaba, who felt that the exploration of characters was an endless journey, type was not a mere symbol but a reflection of human culture and sensibility itself. His fascination drove him to look beyond Western traditions, exploring the scripts of Asia, Africa, and various ethnic minorities, seeking to understand how they originated and lived within people’s lives.

This quest led to a pivotal encounter with the Dongba script in Lijiang, China. Used by the Naxi people, Dongba is a rare surviving pictographic system where the drawn form directly represents its meaning—a mountain’s shape indicates ‘mountain.’ Unlike abstract alphabets or kanji, this script functions to record prayers and stories, leaving a powerful impact on Asaba.

He contrasted Dongba’s symbolic, poetic, and even “imperfect” nature with the modern design world, which judges characters based on readability and communication efficiency. The script confirmed for Asaba that type is fundamentally intertwined with the human endeavor.

His commitment to this belief was crystallized when he sought to acquire a Dongba scripture locally. Discovering none existed in Japan, he spent all his money at an antique shop in Lijiang to obtain one. This act underscored his conviction that characters are “living entities,” not just data.

The experience of seeing the script in its cultural context—listening to the language and observing the rituals—resolved him to incorporate this non-abstract power of characters into his own artistic expression.

西武百貨店「おいしい生活」(1982年)

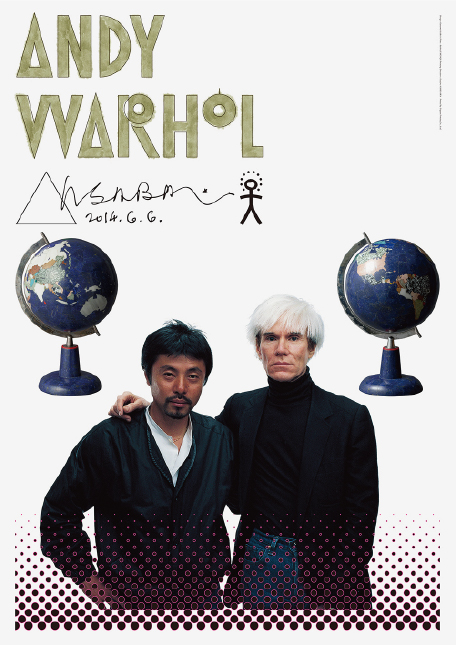

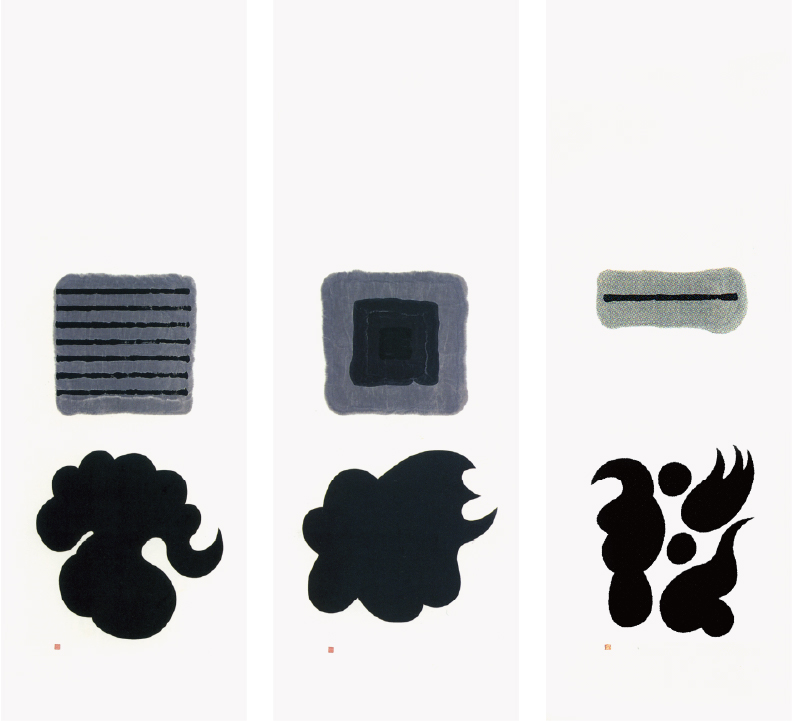

GRAPHIC TRIAL 2014 (2014年)

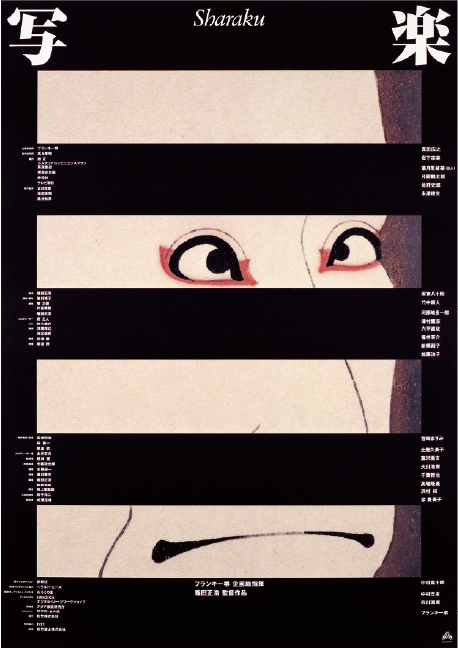

映画「写楽」(1994年)

異文化の文字体験を活かしたグラフィックデザインが、人と広告表現を育てていく。

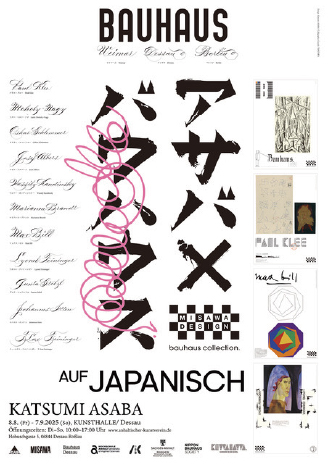

Katsumi Asaba Bauhaus

auf Japanisch (2025年)

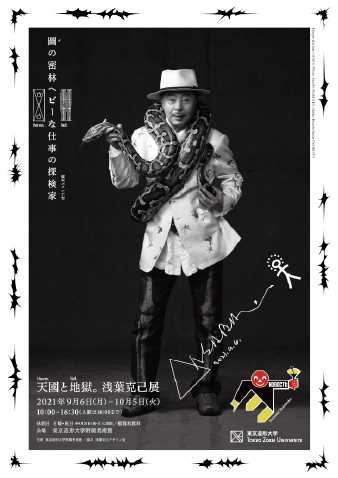

天国と地獄。浅葉克己展(2021年)

「祈りの痕跡。」展(2008年)

ステップインプラン(2003年)

トンパ文字に出会った浅葉さんは、その魅力を自分のグラフィックデザインに活かし始める。山は山の形に描かれ、その造形がそのまま意味になるこの文字は、近代的なフォントにはない根源的な表現の仕方が息づいている。それを自分の表現へと昇華していく。

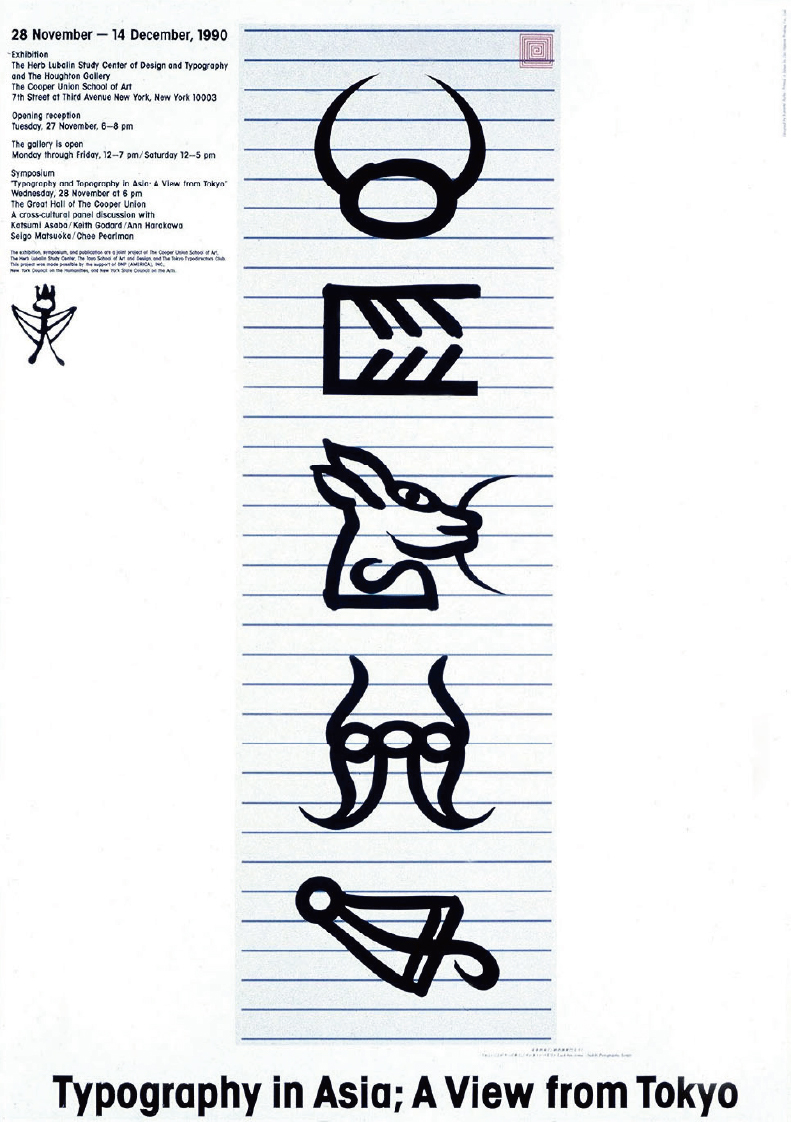

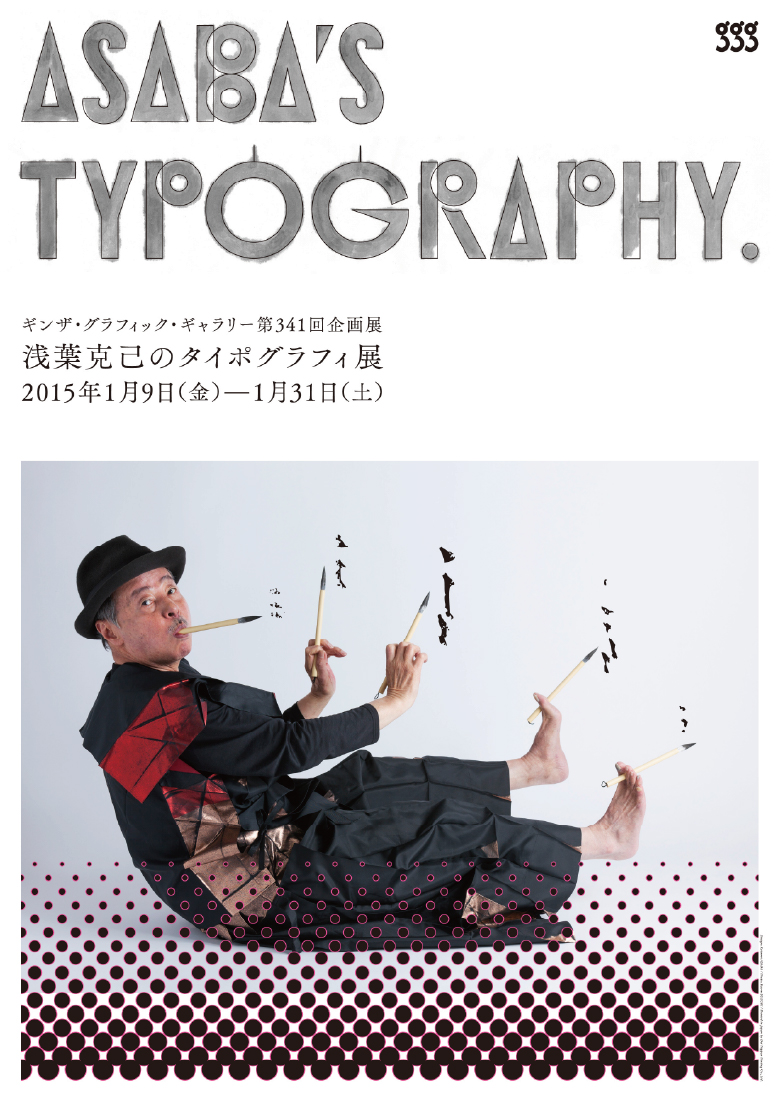

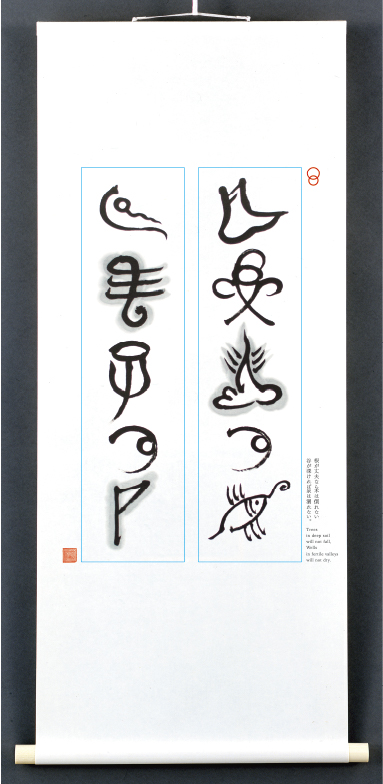

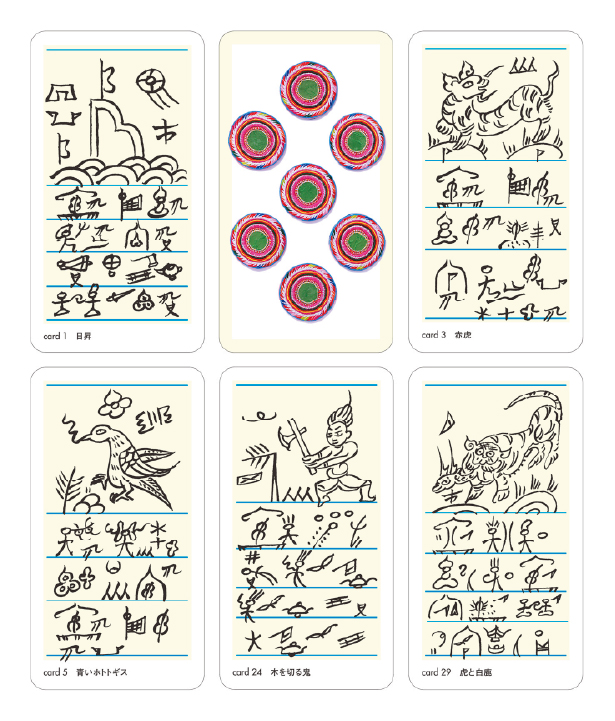

帰国後、浅葉さんが手がけた広告などのポスター作品は、文字を視覚造形として扱う独自の姿勢が一層鮮明になっていった。また、広告の現場にとどまらず、浅葉さんは展覧会を通じてトンパ文字の魅力を広めた。1990年「ギンザ・グラフィック・ギャラリー」の『アジアの文字』展では、アジア各地の文字を造形的にとらえた作品を発表し、その多様性と美を可視化。2008年には「21_21 DESIGN SIGHT」で『祈りの痕跡。』展を開催。現地で収集した経典や自作を展示するだけでなく、来場者が筆をとりトンパ文字の格言を書いて掛け軸に仕立てるワークショップを行った。観客は “見る文字” から “書く文字” へ体験を移し、浅葉さんの思想を身体で理解することになった。

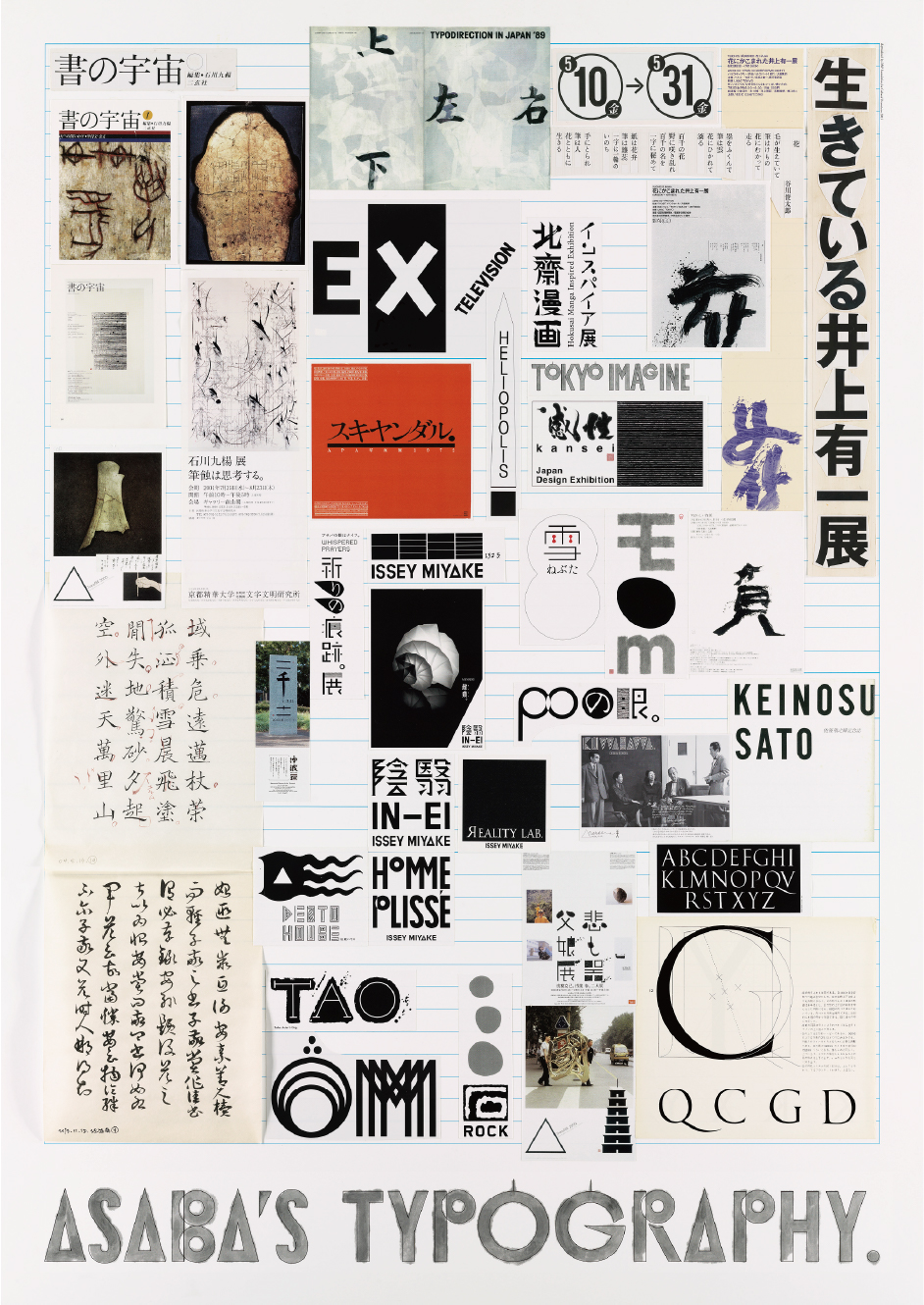

また浅葉さんは日本のタイポグラフィをレベルアップさせるための活動も多くしている。1987年に設立した東京タイプディレクターズクラブでは、国際的なネットワークを構築しながら公募展や作品集を通して世界の文字表現を紹介し、タイポグラフィの新たな可能性を提示。浅葉さんはこの場を、文字を単なる実用フォントではなく文化的営みの象徴としてとらえるための拠点とした。

教育の場でも同様で、かつて多摩美術大学で教鞭をとっていた浅葉さんは講義において、学生にしばしば「文字は単なる技法ではない」と語りかけていた。文字は情報の器にとどまらず、人類の歴史や祈り、日常の痕跡を映し出す文化的存在である。そうした視点を繰り返し示しながら、若い世代にタイポグラフィを “造形のテクニック” ではなく “人間の営みを考える手がかり” として捉えることを促した。そこには、トンパ文字との出会いから得た洞察が脈打っているように思える。

展覧会や書籍以外で浅葉さんが手がけた広告やポスターに、トンパ文字そのものが描かれたことはなかった。しかし、トンパ文字に出会った以降の作品の多くには、“形が意味を先導する” というトンパ文字からの学びが確かに息づいている。

浅葉さんは広告を「情報の装置」としてではなく「生きた造形」として位置づけた。その姿勢は、地球文字探検家としての旅と、アートディレクターとしての営みが結びついた稀有な実践である。広告の枠を超えて、文字を文化の証として提示し続けた浅葉さんの仕事は、いまなおタイポグラフィの核心を問い直し、私たちに「生きた文字」の存在を思い起こさせている。

Graphic design informed by encounters with the scripts of other cultures cultivates both people and the language of advertising.

Upon encountering the Dongba script, Asaba began to integrate its unique appeal into his graphic design. This script, where form directly embodies meaning (a mountain is simply drawn as a mountain), held a primal expressiveness absent in modern fonts, which he sought to elevate into his own art.

After returning to Japan, his posters and advertisements showed an increasingly clear commitment to treating type as a powerful visual form. He also spread the allure of Dongba through exhibitions. Notably, his 2008 “Traces of Prayer” exhibition featured a workshop that fundamentally shifted the audience’s experience from passively “seeing characters” to actively “writing characters,” allowing them to physically embody Asaba’s deep conviction.

Asaba dedicated himself to raising the standard of Japanese typography. As a co-founder of the Tokyo Type Directors Club (TDC) in 1987, he introduced global typographic expression and championed the view of characters as cultural symbols, not mere functional tools.

Similarly, while teaching at Tama Art University, he emphasized that characters are not just technical skills, but cultural entities that reflect human history and prayer. He urged students to see typography as a “clue to understanding human endeavor.”

While the Dongba script itself rarely appeared in his commercial work, the core lesson that “form leads meaning” undeniably shaped his subsequent creations.

Asaba positioned advertising not as an “information device” but as a “living form.” This practice—a rare fusion of his life as a “character explorer” and his art direction—continues to challenge the core of typography and reminds us of the existence of “living characters.”

Typography in Asia: A View from Tokyo(1990年)

浅葉克己のタイポグラフィ展(2015年)

トンパ格言(2010年)

トンパタロットカード(2008年)

地球文字探検家。(2004年)

「書」とタイポグラフィを結び、浅葉克己の表現は多くのクリエイターに影響を与え続ける。

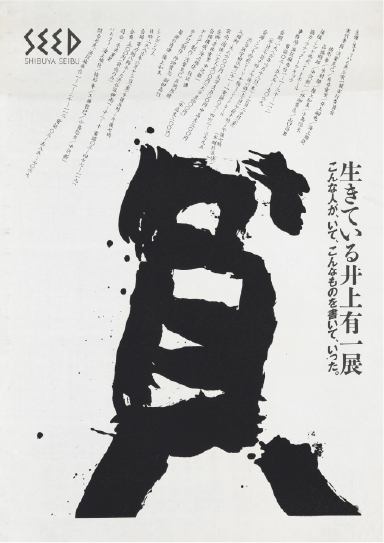

生きている井上有一展(1986年)

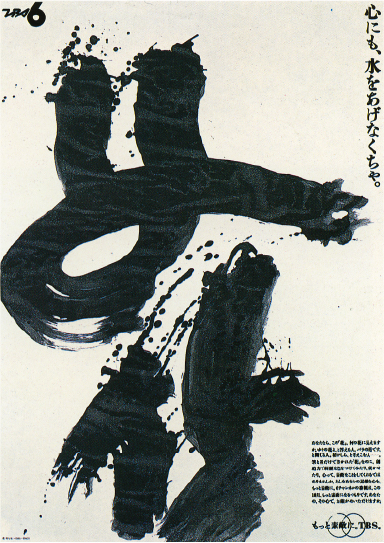

TBS 井上有一花(1988年)

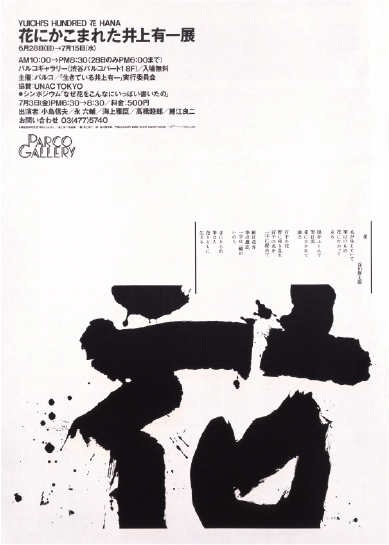

花にかこまれた井上有一展(1987年)

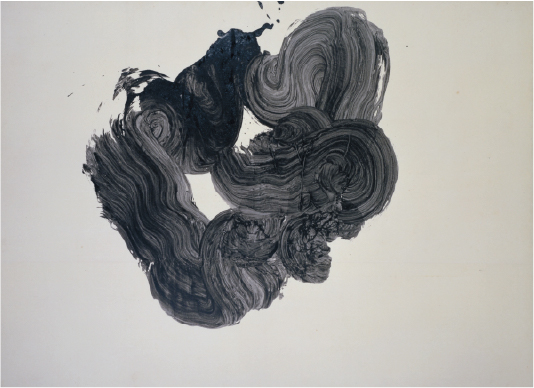

日本のグラフィックデザインを牽引してきた浅葉さんは、「書」への関わりも大切にしてきた。若い頃から漢字の骨格や古代文字の抽象化に魅せられたという浅葉さん。均整のとれた活字よりも、途切れ、滲み、掠れるといった変化を見せる「書」に惹かれていく。

そうした浅葉さんの「書」の探究を深めたのが書家である石川九楊。「書は文字ではなく言葉を書く芸術である」と捉える石川は、筆と紙の接点に生じる筆蝕 “速度・深度・角度・力” の体験性をこそ価値の源泉と説く。その思想に共鳴した浅葉さんは石川九楊の門下生となり、直接的に「書」の鍛錬を受ける。

トンパ文字、そして石川九楊との出会い。このことが浅葉さんのタイポグラフィに大きな影響を与え、そうして生まれた数々のポスターや広告作品は日本のグラフィックデザインを刺激し、進化させた。

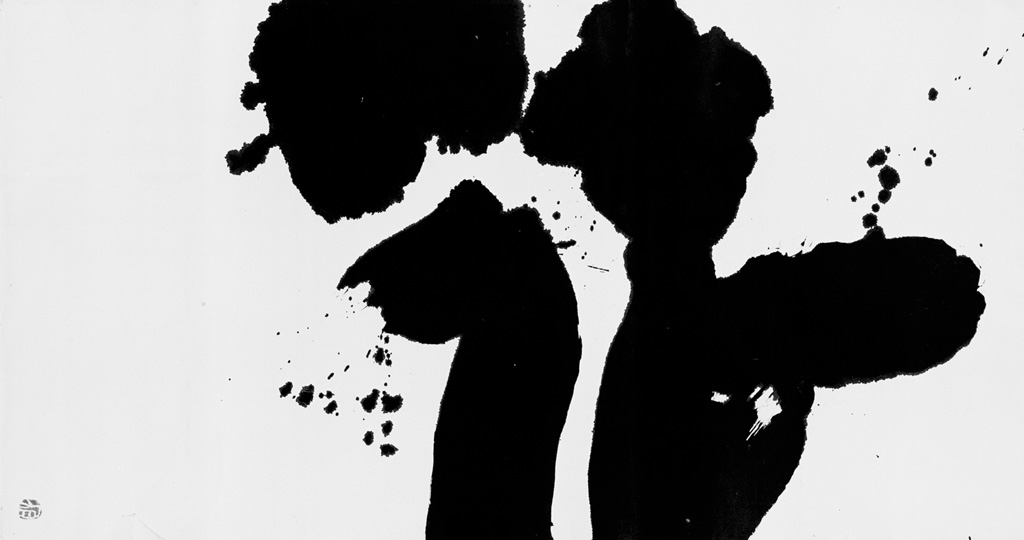

浅葉さんのグラフィックデザインを見ると、「書」との関わりで目を惹くのが井上有一の書を使った『生きている井上有一』展のポスター。この頃、浅葉さんは糸井重里や緒形拳、中沢新一、細野晴臣らといったジャンルを越えた有志とともに「生きている井上有一の会」を結成。展覧会を開催させるなどで井上有一の「書」を世の中に広めた。

浅葉さんの大きな功績のひとつに、書とタイポグラフィを融合させたことがある。欧米的なモダンデザインが無機質な機能美を志向するのに対し、浅葉さんは「書」との関連をもったタイポグラフィにより、東洋的な精神性と身体性を前面に押し出した。「書」の持つアジア的な感覚をグラフィックデザインの土壌に根付かせたのだ。

浅葉さんと「書」の関係を振り返るとき、“文字を書く” という行為が、情報伝達にとどまらず、文化や精神を担う行為であることを改めて認識する。そして浅葉さんの作品は、未来に向けてもなお、「書」の力を現代のデザインに活かす可能性を指し示している。

浅葉さんは現在も、日記や図のスケッチと並行して毎朝の臨書を日課とし、唐代楷書などの古典に挑み続けているという。ここでの鍛錬が、広告やポスターの一点に凝縮される決定的な線へと還流する。書は仕事の“裏”ではなく、仕事そのものを支える基礎体力なのだ。

そうして、浅葉さんが生み出す “じゆうな じ” はグラフィックデザインの未来を、これからも広げていく。

Bridging calligraphy and typography, Katsumi Asaba’s practice continues to shape generations of creators.

Asaba, a leader in Japanese graphic design, was deeply committed to calligraphy. He preferred the expressive, variable lines of shodō over uniform type, having been fascinated by the structure of ancient scripts since his youth.

Calligrapher Kyūyō Ishikawa deepened Asaba’s study. Ishikawa taught that shodō is the art of writing words, with its value lying in the physical experience of the brushstroke (speed, depth, angle, force). Asaba became his disciple to receive direct training.

The encounters with the Dongba script and Ishikawa greatly influenced Asaba’s typography, and his resulting posters and ads stimulated and evolved Japanese graphic design.

A key example is the poster for the Living Yu-ichi Inoue exhibition. Asaba formed an association with cross-genre enthusiasts to organize exhibitions and promote Inoue’s calligraphy to the public.

One of Asaba’s major achievements was the fusion of calligraphy and typography. While Euro-American modern design aimed for sterile, functional beauty, Asaba injected an Oriental spirituality and physicality through shodō-related typography, effectively rooting the Asian sensibility of calligraphy within the soil of graphic design.

Reflecting on Asaba’s relationship with shodō, we are reminded that the act of “writing characters” transcends mere information transfer to become an act that carries culture and spirit. His work continues to demonstrate the lasting potential for applying the power of calligraphy to contemporary design.

Even today, Asaba practices rinsho (copying classics) daily. This discipline becomes the decisive line in his work; calligraphy is the basic physical strength supporting his design.

The “Typography Unbound” he creates will continue to expand the future of graphic design.

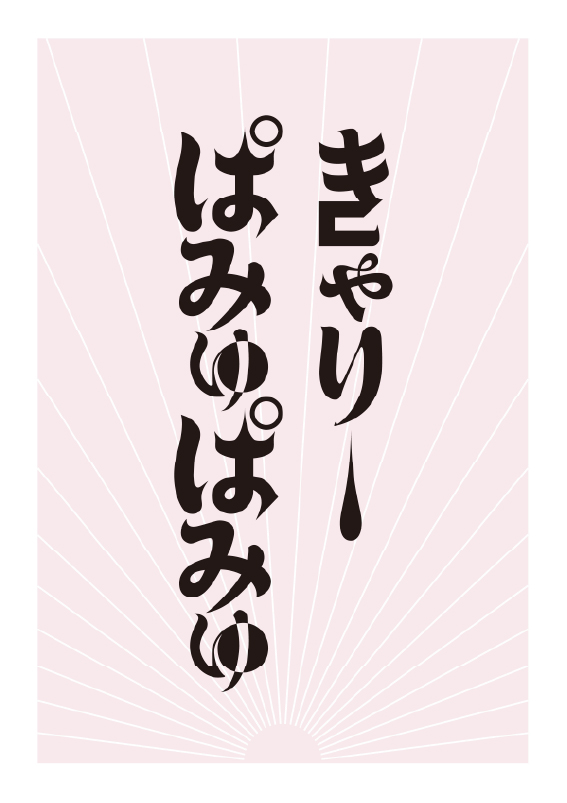

「きゃりーぱみゅぱみゅに捧ぐ」にほんごっ子(2013年)

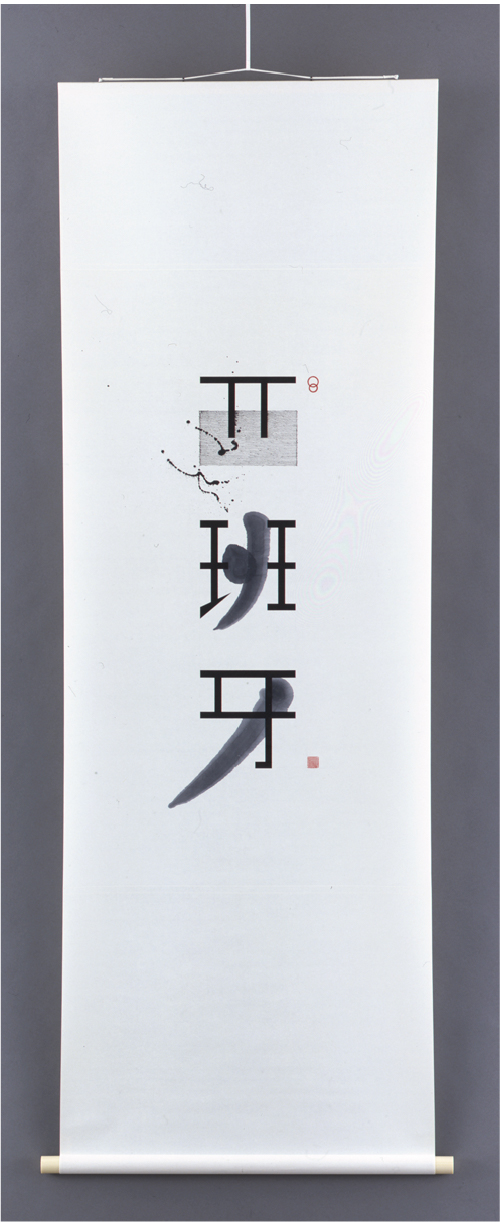

西班牙(2004年)

SABA’S COLLAGE. (2016年)

井上有一の書が広告を変えた時代。松濤美術館で体感する文字とデザインの響き。

Feature | 2025.10.24

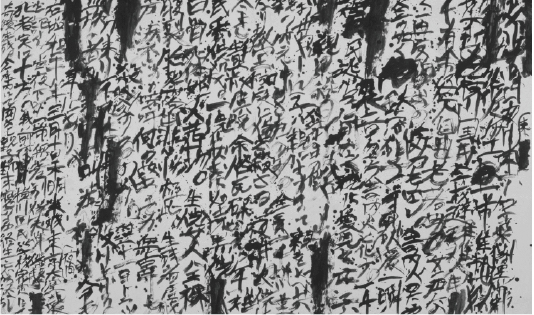

日本の広告表現が大きく揺れ動いた1970年代から80年代、伝統的な「書」と現代的なグラフィックデザインはどのように響き合い、新しい表現の可能性を切り拓いたのか。その問いに応える展覧会が「井上有一の書と戦後グラフィックデザイン 1970s-1980s」。

没後40年を迎えた前衛書家・井上有一の仕事を軸に、当時のグラフィックデザイナーたちがどのように彼の書に触発され、広告やポスター、印刷物の中でそのエネルギーを翻訳していったのかを浮かび上がらせる展覧会となっている。

会場には、『貧』や『噫横川国民学校』をはじめとした代表作が並び、初期の『愚徹』『花』『母』なども含め、前期・後期で作品を数点入れ替えながら紹介される。

墨が紙に叩きつけられた瞬間をそのまま封じ込めたような作品は、伝統的な書の均整のとれた美とは一線を画し、観る者に生々しい衝撃を与える。さらに本展が注目するのは、こうした作品が美術館の中に留まるのではなく、1970年代から80年代の広告やグラフィックデザインの領域で強い影響力を発揮した点。

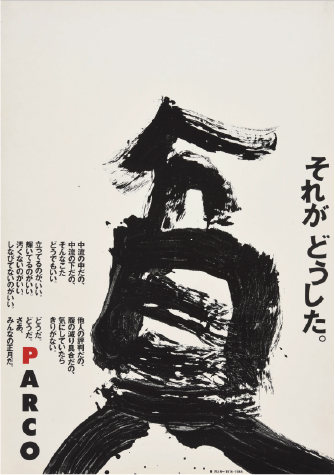

高度経済成長を背景に商業広告が洗練されていった時代、デザイナーたちは井上有一の「荒々しい線」「即興の痕跡」「墨の滴り」を広告表現に取り込み、消費社会へと強く、印象的な訴求を試みた。1986年には『生きている井上有一』展が開催され、また浅葉克己、緒形拳、細野晴臣ら様々な表現者が「生きている井上有一の会」を結成、井上有一の書を現代に蘇らせようとした。この動きのなかで制作されたパルコの「1986年正月/貧」ポスターは、井上有一の書を大胆に広告へ導入した象徴的な例。猛々しく、力強い、巨大な筆跡を相手にしたのはアートディレクターの井上嗣也。そしてコピーライターは糸井重里。当時を代表するクリエイターが井上有一の書という怪物と格闘し、完成度の高いグラフィック作品をつくりだした。

井上有一自身は「弟子を持たない」姿勢を貫いたといわれているが、その表現はグラフィックデザイナーをはじめとしたクリエイターたちによって引き継がれ、広告という公共空間の中で再生産された。

会場を巡ると、井上有一の作品がいかに広告表現の刷新に寄与したかが実感できる。整然としたモダンデザインの流れに抗うように現れた墨の勢いは、浅葉克己や福田繁雄らをはじめとする多くのデザイナーに強い刺激を与え、商業と芸術の間に新しい道筋を開いた。デジタル化が進み、整ったフォントが日常を埋め尽くす現代においてこそ、井上有一の生きた筆跡は新鮮で、広告やデザインが文字に託してきたメッセージの重みを再考させる。

単なる回顧展ではなく、書と広告が交わった豊穣な時代を追体験し、未来のデザインにおける文字表現の可能性を考える機会になる必見の展覧会だ。

The era when Yui-chi Inoue’s calligraphy transformed advertising.

Experience the resonance of characters and design at the Shoto Museum of Art.

From the 1970s to the 80s, a period of great change in Japanese advertising expression, how did traditional “sho” (calligraphy) and modern graphic design resonate with each other and pave the way for new possibilities in expression? An exhibition titled “INOUE Yu-ichi’s Calligraphy and Postwar Graphic Design in 1970s-1980s” seeks to answer this question.

Centered on the work of avant-garde calligrapher Inoue Yu-ichi, who passed away 40 years ago, the exhibition illuminates how graphic designers of the time were inspired by his calligraphy and translated its energy into advertisements, posters, and other printed materials.

The venue will feature his representative works, including “Hin” (Poverty) and “Aa Yokogawa Kokumin Gakko” (Ah, Yokogawa National School), along with early pieces like “Gutetsu” (Foolish Iron), “Hana” (Flower), and “Haha” (Mother), with some works being rotated between the first and second halves of the exhibition.

His works, which seem to encapsulate the very moment ink was slammed onto paper, stand in stark contrast to the balanced beauty of traditional calligraphy, delivering a raw and visceral shock to the viewer. This exhibition also draws attention to how these works didn’t remain confined to museums, but exerted a powerful influence on advertising and graphic design from the 1970s to the 80s.

In an era of sophisticated commercial advertising driven by rapid economic growth, designers incorporated INOUE Yu-ichi’s “rough lines,” “traces of improvisation,” and “ink drips” into their work,attempting to make a strong and impactful appeal to consumer society. In 1986, the exhibition “The Living INOUE Yu-ichi” was held, and various artists, including Katsumi Asaba, Ken Ogata, and Haruomi Hosono, formed the “The Living Inoue Yuichi Association” to bring his calligraphy back to life in the modern age.

The Parco poster for “1986 New Year / Poverty” created during this movement is an iconic example of the bold introduction of INOUE Yu-ichi’s calligraphy into advertising. The ad-art director, Tsugiya Inoue, and copywriter, Shigesato Itoi, challenged the fierce, powerful, and massive brushstrokes, creating a highly polished graphic piece.

Though INOUE Yu-ichi himself is said to have maintained a stance of “having no disciples,” his expression was carried on by graphic designers and other creators, and was reproduced within the public space of advertising.

As you walk through the venue, you will feel firsthand how INOUE Yu-ichi’s work contributed to the revitalization of advertising expression. The momentum of the ink, which appeared to defy the flow of neat modern design, provided strong inspiration for many designers, including Katsumi Asaba and Shigeo Fukuda, and opened a new path between commerce and art. In the present day, where digital technology and perfectly aligned fonts fill our lives, INOUE Yu-ichi’s lively brushstrokes feel fresh and prompt us to reconsider the weight of the messages that advertising and design have entrusted to words.

This is a must-see exhibition that is more than a simple retrospective; it’s an opportunity to re-experience a fertile period where calligraphy and advertising intersected, and to consider the possibilities of character expression in future design.

『井上有一の書と戦後グラフィックデザイン 1970s-1980s』

2025年9月6日(土)〜 2025年11月3日(月・祝)

前期:9月6日(土)~10月5日(日)

後期:10月7日(火)~11月3日(月・祝)

※会期中、一部展示替えあり

【休館日】

月曜日(ただし9月15日、10月13日、11月3日は開館)、

9月16日(火)、9月24日(水)、10月14日(火)

操上和美 《井上有一肖像》

1984年8月31日撮影 個人蔵

井上有一 《愚徹》 1956年 墨・紙 国立国際美術館蔵 Ⓒ UNAC TOKYO

井上有一 《母》

1961年 墨・紙 京都国立近代美術館蔵 Ⓒ UNAC TOKYO

井上有一 《噫横川国民学校》

1978年 墨・紙群馬県立近代美術館蔵 Ⓒ UNAC TOKYO

井上有一 《花》 1957年 墨・紙 個人蔵 Ⓒ UNAC TOKYO

井上嗣也「1986年正月/貧」ポスター、

1986年 AD・D:井上嗣也

A:井上有一(ウナックトウキョウ)

C:糸井重里 PL:對馬壽雄

ADV:パルコ 個人蔵

井上嗣也「COMME des GARÇONS

’96-’97AUTUMN WINTER DM」

1996年 AD・D:井上嗣也

A:井上有一(ウナックトウキョウ) CD:川久保玲

ADV:COMME des GARÇONS

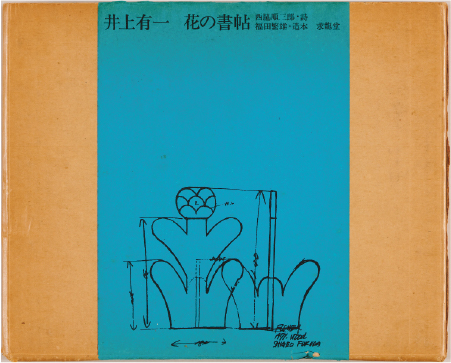

井上有一著・福田繁雄造本『花の書帖』求龍堂

1971年 個人蔵