ピアノの詩人・ショパンに対し、ピアノの魔術師・フランツ・リスト。

Column|2025.4.24

Text_Kotaro Sakata

写真提供:金子三勇士 写真_©Seiichi Saito

リスト画写真坂田康太郎

今、空前のピアノブームが来ているようだ。昨今の高学歴でありPOPSをピアノで奏でるアーティストが出現していることも要因であろう。それ以来、ピアノのコンサートが全国各地で大盛況となっている。今まで、クラシック音楽に馴染みのなかった方も、コンサートホールに足を運んで、文化・芸術が生活に広がることは生きる源になり豊かな自分に成ることを感じることでしょう。

かつてクラシックブームは定期的に起こっている。その立役者の一人が、フジコ・ヘミングであろう。彼女を襲った悲劇をNHKが特集番組として取り上げ、悲劇のヒロインの奏でる、リスト作曲『ラ・カンパネラ』が見る人の心を掴んだ。しかし、ピアノの魔術師フランツ・リストの代表的な超絶技巧のこの曲は、5分ほどの小品でありながら連打、跳躍、10本の指とペダルを駆使し演奏しなければならないので、並みのピアニストでは弾き得ない。フジコさんの奏でる『ラ・カンパネラ』は、難所で極端にテンポが遅くなるなど、クラシック音楽通からは否定され、判官贔屓の聴衆と敵対した。今では、懐かしい出来事だ。

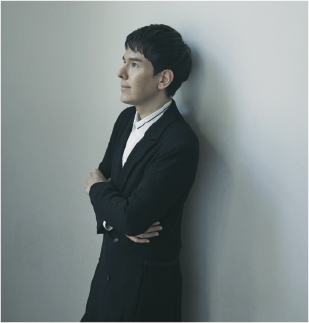

では、今の時代に聞くべき本物のリスト弾きピアニストをご紹介しよう。ピアニスト:金子三勇士である。彼は、日本人の父とリストの母国であるハンガリー人の母のもとに生まれ、6歳よりハンガリーのピアノ教育第一人者チェ・ナジュ・タマーシュネーに師事する為、単身ハンガリーに留学し祖父母の家よりバルトーク音楽小学校に通い、11歳に飛び級で国立リスト音楽院大学特別才能育成コースに入学し、リスト本人の直系に弟子入りし、リストのDNAを心身に刻み込んだ。大学終了後に帰国し東京音楽大学付属高等学校2年に編入する逆転進学という神業を成し遂げ、リストと並ぶ、ハンガリーの作曲家を冠したバルトーク国際ピアノコンクールで見事優勝を果たす。帰国したときは、漢字ドリルで日本語を勉強しながら日本語を習得し、英語、ハンガリー語など数か国語をネイティブに話し、その温厚でノーブルなキャラクターと対照的な超絶技巧を駆使したフランツ・リストの超絶技巧曲を弾きこなす彼の姿は、パリやウィーンの社交界を席巻したアイドル的存在のリスト本人と重なりあう。金子三勇士の愛されるキャラクターは、NHKの番組司会者に抜擢されるという肩書からも分かるように、他のアーティスト、芸術家へのリスペクトと後進へ背中を見せる姿などから人の心を掴んで止まない。

2021年には日本デビュー10周年を迎え、2022年3月にサントリーホールでソロ・リサイタル「原点×挑戦」を開催し、ベートーベン『第九』・リスト編曲の超・超絶技巧の編曲版を金子三勇士自身がさらに編曲し、自身の演奏を自動演奏再現したスタインウェイ spirioを持ち込み、同スタインウエイフルコンサートモデルを自身で弾き、20指を一人で奏でるという離れ業で大絶賛を受ける。同席した筆者も思わず感涙にむせぶ。この大成功を記念し、ドイツ・グラモフォンより新譜CD「フロイデ」もリリースされた。現在、キシュマロシュ名誉市民でありスタインウェイ・アーティストである、金子三勇士の奏でる『ピアノの魔術師:フランツ・リスト』は聞き逃せない。

If Chopin was the poet of the piano, then Franz Liszt was its magician.

We’re in the middle of an unprecedented piano boom—thanks in part to highly educated artists bringing pop music to the keys. Piano concerts are packed across Japan, drawing even those new to classical music into concert halls, where they discover how culture and art can enrich life and lift the soul.

Classical music booms come and go, and one standout from a past wave was Fujiko Hemming. Her tragic story, featured on NHK, and her deeply emotional performance of Liszt’s La Campanella captivated many. Though only five minutes long, the piece demands extreme technical skill—far beyond most pianists. Fujiko’s interpretation, with its dramatic tempo shifts, drew criticism from purists but resonated with fans who admired her vulnerability. Today, that moment feels like a nostalgic piece of music history.

So let me introduce a true Liszt pianist for our times: Miyuji Kaneko. Born to a Japanese father and Hungarian mother, Kaneko moved to Hungary, Liszt’s homeland, alone at age six to study under piano teacher Zsuzsa Cs. Nagy. Living with his grandparents while attending Bartok Elementary School of Music, at the age of 11, he skipped grades to enter The Special School for Exceptional Young Talents of the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. There, he became a direct heir to Liszt’s musical legacy. After graduating, he made the rare leap into the second year of Tokyo College of Music High School and later won the prestigious Bartók International Piano Competition, named after Hungary’s other musical giant. Back in Japan, he studied Japanese from scratch while already fluent in several languages. His kind, noble demeanor contrasts with his breathtaking technique—channeling Liszt’s own superstar charisma. Now a popular NHK host, Kaneko is beloved not only for his talent but for his humility and support of younger musicians.

In 2021, Miyuji Kaneko marked his 10th anniversary since debuting in Japan. The following March, he performed a solo recital at Suntory Hall titled Origin × Challenge, featuring his own re-arrangement of Liszt’s famously complex version of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Using a Steinway Spirio that reproduced his playing alongside his live performance, he pulled off a dazzling “twenty-finger” duet—earning rave reviews. I was in the audience, and I couldn’t hold back tears. To commemorate the success, Deutsche Grammophon released his new album, Freude. Now a Steinway Artist and honorary citizen of Kismaros, Kaneko’s Liszt performances are not to be missed.

オーストリア皇帝フランツ・ヨーゼフ1世と

エリザベート皇后の前で演奏するフランツ・リスト本人画

ピアニスト 金子三勇士

CD『フロイデ』

ジャケット写真:ドイツ・グラモフォン