私的で

知的な空間学。

私的で知的な空間学。

新しく、お気に入りの空間を見つけませんかという話。

誰もがひとつは、お気に入りの空間をもっているのでは。それは自分の部屋だったり、いつものカフェだったり、近所の公園だったりするのかもしれない。近頃では自宅と職場以外の、サードプレイスといわれる場所・空間が話題になったりもする。 今号の「yoff」では “空間” を特集。しかもとても私的で、ちょっと知的な空間の話をセレクト。 渋谷区立松濤美術館で哲学の建築家といわれる白井晟一を知り、横浜のクラシックホテルであるホテルニューグランドの迎賓の心に触れる。そして、写真のなかにある空想の空間に思いを馳せる。 さらに人気コーナー「旅する餃子」シリーズでは、もしスペインに餃子があったら、という妄想レシピが登場。 眺めて、読んで、少しお勉強にもなる今号の「yoff」。あなたのお気に入りの空間が見つかるかもしれません。

『生きる』ための、哲学の空間。

Feature | 2024.05.23

東京渋谷の閑静な住宅街に佇む松濤美術館。

設計者の白井晟一はここに、自分なりの揺るぎない思想と価値観を表現した。

建築は夢だった。マイホームを建てるとき、その家は夢になる。経済成長をしていた日本では、都市に林立するビルは夢を具現化していた。万国博覧会のような国際イベントでは、夢のようなデザインのパビリオンが多くあった。

建築は夢という思いが妄想だと感じだしたのが、2020東京オリンピックに向けての国立競技場建て替えのとき。当初、採用されたザハ・ハディドのプランをみたとき、未来的でスケール感がありワクワクした。しかし、予算の関係か巨大過ぎたためか、それとも政治的な何かがあったからかは知らないが、ザハの案は外される。かわりに採用されたのが隈研吾のプラン。日本らしく木材を多用し、スタジアムにしては品格があり落ち着いている。それはそれで素敵なのだが、しかしザハ案と比べると質素だと感じてしまう。なんだか夢が削がれたような。

そうして気づいてみると、都心のあちらこちらに再開発の波が襲い、似たようなビルが乱立。本当にビルが必要なのかということも含めて疑問に思う。長方形の箱が建ち並ぶ景観には夢がない。なかには麻布台ヒルズの低層部のようにチャレンジングなものもあるが数は少ない。もっと、建築に夢を見たい。そんなことを考えているときに、白井晟一という建築家を知った。人間に内省を促す建築家といわれ、彼がつくった空間には哲学が息づいているという。面白そうだ。

白井晟一が手がけた建築物は個人邸から公共施設、銀行など多くある。有名なところでは渋谷区立松濤美術館や港区麻布台のノアビル、佐世保市の親和銀行本店。どれも堅牢なイメージがあり、見るからに小難しそうで、だからこそ楽しめそうだ。百聞は一見にしかずなのが建築。さっそく松濤美術館にお邪魔することにした。哲学の空間、そこで夢を見ることはできるか。

A philosophical space for living.

To me, architecture was the stuff of dreams. When you build your own home, it embodies a dream. During Japan’s economic boom, the skyscrapers filling the cities represented dreams, and international events like world expos showcased pavilions with dream-like designs.

I began to feel that architecture as dreams was a fantasy around the time of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, when the National Stadium was being rebuilt. I was initially thrilled by Zaha Hadid’s futuristic, grand plan. However, due to budget constraints, its large scale, or political reasons, her design was discarded. In its place, Kengo Kuma’s plan featuring traditional wood and exuding dignity and tranquility was adopted. Although beautiful, it felt modest compared to Hadid’s vision, like a scaled-down dream.

Waves of redevelopment sweep through various areas of Tokyo, with similar buildings cropping up here and there, raising the question of whether all these rectangular boxes lacking any dreamlike quality are truly necessary. While there are adventurous designs like the low-rise section of Azabudai Hills, they are few. Longing for more dream-like architecture, I discovered architect Seiichi Shirai. Known for fostering introspection, the spaces he creates are imbued with philosophy, making them uniquely intriguing.

Seiichi Shirai’s portfolio ranges from private homes to public facilities and banks, with standout projects such as the Shoto Museum of Art, the NOA Building in Azabudai, and the Shinwa Bank headquarters in Sasebo City. Each project carries a robust and somewhat imposing image, enhancing their appeal. Believing that seeing is believing, I was compelled to visit the Shoto Museum of Art to experience the philosophical space and find the dream within it.

渋谷区立松濤美術館

「異端の作家」が手がける美術館。

白井晟一は1905年、京都に生まれた。高校を卒業後、ドイツのハイデルベルグ大学に入学。第一希望の専修は「哲学科美術史」だったという。その後、ベルリン大学に移る。パリへと赴くことが多かった白井はその頃、フランスの作家であったアンドレ・マルローや当時パリに滞在していた小説家の林芙美子、文芸評論家の小松清らと親交をもつようになる。

1933年、28歳で帰国してからしばらく、東京の山谷で孤児の世話をし、その後は千葉の山中で仲間たちと禅道場と兼ねたような共同生活をおくるがすぐに解散。1935年には義兄の自宅とアトリエの、実質的な設計のほとんどを行い、それが建築家としての最初の仕事となる。

白井が建築家として活躍をはじめた頃、ヨーロッパからモダニズム建築が入りだす。日本の建築はモダニズム建築と対峙しながらその在り方を問い、やがてモダニズムがメインストリームとなっていく。そんななか、白井が取った立ち位置はモダニズム建築と一線を画すものだった。独自の思想による建築物を次々と発表し、「異端の作家」「哲学の建築家」などと呼ばれるようになる。

そんな白井が晩年、75歳のときに手がけたのが渋谷区立松濤美術館。その年齢からして、ここには白井の建築に対する思想・哲学が詰まっていると思われ、実際にその要素は館内のいたるところに見ることができる。

1981年に開館した松濤美術館。閑静な住宅街のなかにあることから、地上2階、地下2階の4階構造となっている。外から見ると、窓が少なく、ひっそりとした佇まい。一方で建物内部の中心には円形の大きな吹き抜けが設けられていて開放的、さらに下部には噴水がある。この吹き抜けは大きな窓に面していて、建物内のどの階にいてもたっぷりの採光が楽しめて気持ちいい。しかしこの吹き抜けと噴水は、美術館にはあり得ないものだという。それはどういうこと?

A museum designed by a maverick artist.

Seiichi Shirai was born in 1905 in Kyoto and studied Philosophy and Art History at Heidelberg University in Germany before transferring to the University of Berlin. While in Europe, he frequently visited Paris where he befriended writer André Malraux, novelist Fumiko Hayashi and literary critic Kiyoshi Komatsu.

In 1933, at age 28, Shirai returned to Japan, initially caring for orphans in Tokyo’s Sanya area. Later, he moved to the mountains of Chiba to start a Zen dojo with friends, which quickly disbanded. In 1935, he designed his brother-in-law’s home and atelier, marking his first architectural project.

As Shirai embarked on his architectural career, modernist architecture was emerging in Japan from Europe. Japanese architecture, grappling with modernism, began to reassess its approach, and modernism eventually became predominant. Yet Shirai’s stance distinctly stood apart from modernism. One after the next, he unveiled buildings that reflected his unique ideology, earning him the titles of “the maverick artist” and “the philosopher-architect.”

One of his later projects, the Shoto Museum of Art in Shibuya, was completed when he was 75. This building is considered a culmination of Shirai’s architectural philosophy and ideology, elements of which are evident throughout the museum.

The Shoto Museum of Art, opened in 1981, stands in a quiet residential area and spans four floors: two above and two below ground. Its exterior appearance is subdued with few windows. Inside, the central feature is a large circular atrium that creates a welcoming, open space, with a fountain at its base. This atrium is lined with large windows that flood each floor with natural light. However, both the atrium and fountain are unusual for a museum, raising questions about the intent behind these features.

a.吹き抜けに面している窓は、美術作品を保護するために通常は塞がれている。(撮影:上野則宏)

b.2階の展示室。昔はここでお茶やクロックムッシュなどの食事が楽しめた。

※前橋市の書店「煥乎堂」にある蛇口と同じものが設えられている。

哲学の空間がある建築は夢になる。

作品保護の観点からいえば、「生物が生きるために必要な環境の変化や刺激、例えば降り注ぐ陽光や流れる水は、美術作品の保存状態を損ないます。ですので美術館内は、生々流転なるものを止めた、いわば時間が停止した空間であることが良いのです」。そう語るのは松濤美術館の学芸員である木原天彦氏。「白井は生き物に必要な要素をあえて、美術館に取り入れた。それがこの吹き抜けと噴水です。水、光、そしてアート、それらは等しく、生きていくために欠かせないものということなんだと思います」。

他にも、白井のこだわりは数え切れないほどある。まず、エントランス脇の蛇口。そこにはラテン語で「清らかな泉」と書かれていて、美術館が、知恵が湧きでる泉だということをメッセージしている。

館内に足を踏み入れると、オニキスを薄くスライスした光天井が設けられている。このように天から降り注ぐ光は、ヨーロッパのキリスト教的な空間づくりから影響を受けているのだろうか?先にある扉を開けると、話にでてきた中央の吹き抜けにかかるブリッジへとでる。円を描くオープンエアな空間、下を見ると噴水がきらめきながら弾け、まさに生命の息吹を感じる。

2階の展示室にも「異端の作家」らしいつくりがされている。この建物は鉄筋コンクリート造りだが、ここには木の柱と梁がある。しかしよく見ると、その柱と梁の位置がずれていて、これでは構造物を支える役目は果たさない。つまり、これらはフェイク。梁のなかは空調ダクトが通っている。なぜこんな悪戯のようなことをしたのか?木原氏が答えてくれた。「これはモダニズムに対する反発だと思います。正しい構造にある美しさを礼賛するモダニストを嘲笑っている。白井のこういったところが、後のポストモダンの人々から支持されるようになります」。なんともパンクな建築家だ。

こうして木原氏の説明を受けながら館内を巡っていると、まるで白井の脳内を歩いている気分になる。白井の建築や美術に対する深い想いが随所に表現された館内は、まさに哲学の空間。久しぶりに建築にある夢を見た気がした。

Architecture with philosophical spaces engenders dreams.

Amahiko Kihara, a curator at the Shoto Museum of Art, explains that while environmental factors such as sunlight and flowing water are vital for life, they can harm art. Museums, therefore, should be static spaces that pause these dynamic elements, effectively suspending time. Yet shirai intentionally integrated these life-essential elements—water, light—into the museum through features like the atrium and fountain, viewing them as indispensable as the art itself.

Shirai’s meticulousness is evident throughout the museum. For instance, the faucet by the entrance, inscribed in Latin with “pure spring,” symbolizes the museum as a source of wisdom.

Stepping inside the museum, one is greeted by a luminous ceiling consisting of thin onyx panels. Could this light streaming down from the heavens be influenced by European Christian spatial design? A door leads to a bridge over the central atrium mentioned earlier. The open-air circular space, looking down onto the sparkling fountain, feels like the breath of life.

The second-floor exhibition room features the touches of the maverick artist. Although built with reinforced concrete, this room has decorative wooden pillars and beams that are misaligned and non-structural, merely hiding air conditioning ducts. Curator Kihara explains this playful deception as “a rebellion against Modernism, mocking those who praise structurally perfect designs.” This approach has endeared Shirai to fans of Postmodernism, highlighting his punk spirit.

Touring the museum with Kihara feels like delving into Shirai’s mind. Each space within the museum, imbued with Shirai’s deep architectural and artistic insights, represents a philosophical haven. It was as if I was rediscovering the dreamlike essence of architecture after a long time.

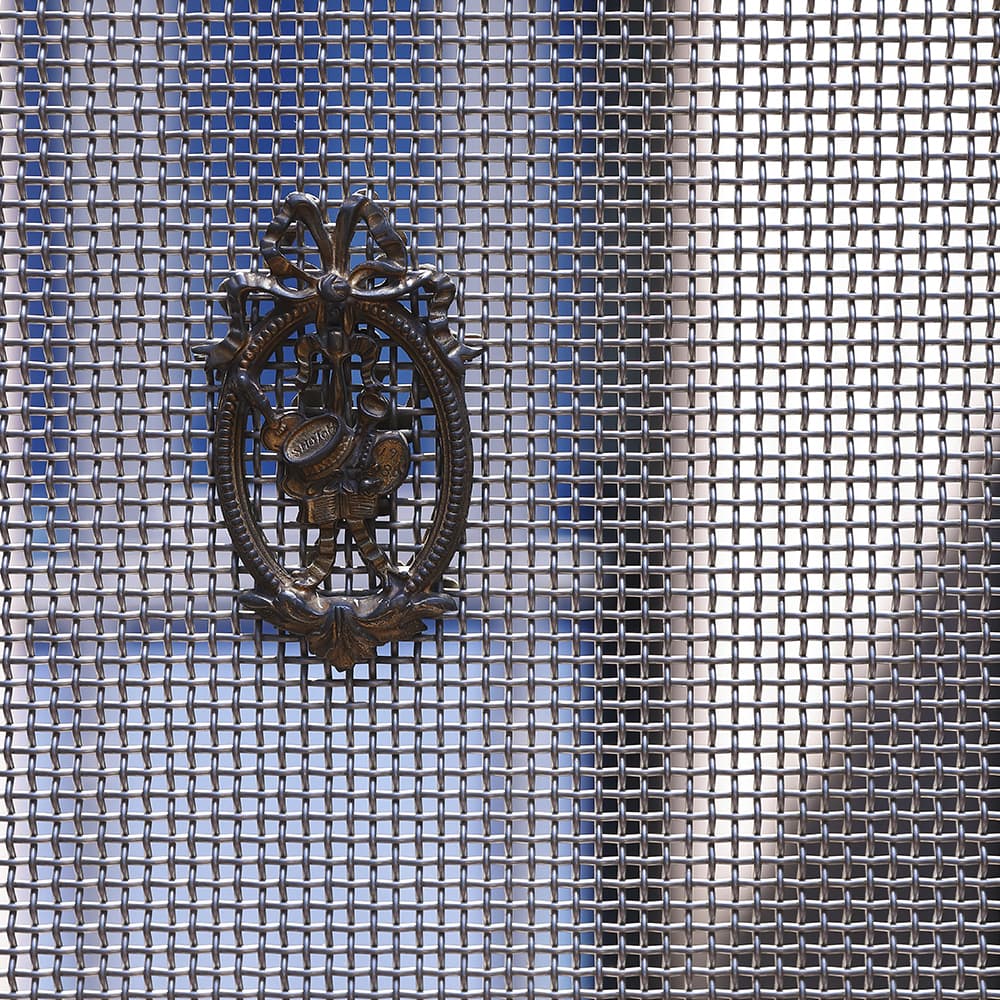

アールヌーヴォーの旗手として知られる奇想のガラス作家、

エミール・ガレの没後120年を記念した展覧会。

国内の個人コレクター所蔵の貴重な作品を中心にガレの足跡を紹介。

没後120年 エミール・ガレ展 奇想のガラス作家

Émile Gallé: The Inspirational Glass Artist

左.エミール・ガレ《花器「地質学」》1889年 個人蔵

右.エミール・ガレ《花器(プリムラ)》1900年頃 個人蔵

2024. 5/8(水)〜 6/9(日)

開館時間:午前10時~午後6時(入館は午後5時30分まで)※毎週金曜日は午後8時まで(入館は午後7時30分まで)

休館日:月曜日

入館料:一般800(600)円

※()内は10名以上及び渋谷区民入館料)

※障がい者及び付き添いの方1名は無料

和と洋が融合した、迎賓の空間。

Feature | 2024.05.23

横浜のクラシックホテルといえばホテルニューグランド。

多くの著名人に愛された歴史ある建造物には、旅人を上質にもてなす迎賓の空間があった。

“おもてなし”といえば、横浜。なんといっても、この地の“おもてなし”には歴史と多くのストーリーがある。日米和親条約締結後、1859年に開港された横浜はそこから、日本を代表する貿易都市として海外からたくさんの人々が訪れるようになる。まだ外国人が珍しい時代、横浜の人たちは試行錯誤しながら、日本流の“おもてなし”で、海を超えてやって来た客人をお迎えしたことだろう。

旅人をもてなすとき、肝心になるのが宿泊施設。長い船旅で疲れたカラダをゆっくりと休めてもらい、さらに日本という異国を楽しんでいただく。そのための、最上のおもてなしの場となったホテルがホテルニューグランドだった。

ホテルニューグランドは1927年、関東大震災から立ち上がろうとしていた横浜を象徴する存在として誕生。当初は喜劇王のチャップリンや野球選手のベーブルースといった海外からの錚々たる賓客たちが宿泊。第2次世界大戦後はGHQによって接収され、マッカーサー元帥も逗留した。その後、1952年に営業を再開。日本が高度成長期を迎え豊かになってきた頃から日本人も盛んに利用するようになった。横浜のラグジュアリーなイメージを具現化することで、多くの財界人や芸能人にも愛されてきたホテルニューグランドは、バーがサザンオールスターズの歌にもでてくるなどで、現代では若い人たちの憧れのホテルにもなっている。

クラシカルな本館に隣接して近代的なタワー館が完成したのが1991年。そして2004年には本館の客室を、2007年には本館ロビーをリニューアル。ただし、リニューアルといっても、すべてを真新しくするような野暮なことはしない。独自の設計・意匠や家具のひとつひとつに気を配り、オープン当時のものはなるべくそのままにしながら、時代の積み重なりが体感できる、クラシカルでモダンな空間をつくりあげた。

ホテルニューグランドの建築としての見所が詰まっているのが本館2階ザ・ロビー。この歴史的な空間はさまざまな発見にあふれている。

A welcoming space where Japanese and Western aesthetics merge.

Yokohama boast a long and storied history of hospitality. Following the Treaty of Kanagawa, it opened its port in 1859, becoming a major trading hub and attracting numerous visitors from abroad. In an era when foreigners were still rare, the people of Yokohama, through trial and error, extended traditional Japanese hospitality to these guests.

Accommodations play a crucial role in hospitality. After lengthy sea voyages, travelers needed a place to rest and experience Japan’s exotic charm. The Hotel New Grand became the epitome of superlative hospitality.

Founded in 1927, the hotel emerged as a symbol of Yokohama’s quest to recover from the Great Kanto Earthquake. Early on, it hosted distinguished foreign guests like Charlie Chaplin, the king of comedy, and baseball legend Babe Ruth. Post-World War II, the hotel was requisitioned by the GHQ, and notably hosted General MacArthur.

After reopening in 1952 during Japan’s rapid economic growth, the hotel saw an increase in Japanese guests. Embodying Yokohama’s image of luxury, it became favored by business leaders and celebrities, and even featured in a song by Southern All Stars, becoming popular even among young people today.

In 1991, a modern tower wing was added alongside the classical main building. Renovations in 2004 and 2007 updated the guest rooms and lobby, respectively, with care taken to preserve the original character as much as possible, creating a space that is both classical and modern and allowing visitors to feel the layers of time.

A key architectural feature of the Hotel New Grand is the grand staircase leading to the second-floor lobby of the main building, a space rich with historical discoveries.

クラシックな家具が置かれた2階ザ・ロビー。

宴会場が使用されているときは立ち入ることができないのでご注意を。

HOTEL NEW GRAND

a.大階段(ホテルニューグランドのシンボル的存在の大階段。ニューグランドブルーと呼ばれる青い絨毯が敷かれている。)

b.本館ザ・ロビー

c.本館ザ・ロビー

ディテールに目を凝らせば、和とアジアが浮かび上がる。

「神は細部に宿る」といったのはドイツのモダニズム建築家ミース・ファンデル・ローエ。その言葉はここ、ホテルニューグランドにもあてはまる。

ホテルニューグランド本館の外観を眺め、中へと一歩入れば、ヨーロッパ調のクラシカルな印象を受ける。古くからここに海外の人たちが出入りしていたことが実感できる、ロマンにあふれた場所だ。

本館に入るとまず、階段がある。ホテルニューグランドのシンボル的存在の大階段だ。 そのまま2階ザ・ロビーへと急いではいけない。この階段をじっくり眺めると、両サイドにフルーツバスケットのオブジェがあるのに気づく。 これは海外のホテルによくあるウエルカムフルーツで、おもてなしの心があらわされている。手摺りのタイルも味がある。イタリア製の手焼きのタイルで一枚一枚、特注されたもの。使用される部分に合わせて湾曲したものや菱形のものなど、さまざまなバリエーションがある。 青みを帯びた美しい色合い。 つるんとしていたり、ちょっとざらつきがあったり、触感もそれぞれ違い、手で触れたときの多彩な味わいが楽しめる。

階段を上がりながら天井へと視線を移すと、そこにあるのは天女奏楽の図が織られたタペストリー。 ん?! ヨーロッパなイメージのホテルニューグランド、なのに天女? さらにタペストリー近くのアーチのなかにもやはり、和風の紋様がある。天井から下がっている照明も和のテイスト。和紙でできていて、僧侶が修行する伽藍にあるようなデザインになっている。

こうして細かく見ていくと、いくつもの日本や東洋が設えてある。しかもそのどれもが、手の込んだもの。海外からの宿泊客は、そんなところを発見することで、エキゾチックな魅力を感じたことだろう。これもひとつの“おもてなし”。ホテルニューグランド本館の空間、その細部には迎賓の心が宿っている。

Japanese and Asian influences emerge from the details.

“God is in the details,” said the German modernist architect Mies van der Rohe, words that apply well to the Hotel New Grand.

Observing the main building’s exterior and stepping inside, one is struck by its classical European style. The place is filled with romance and one can sense the traffic of people from overseas since olden times.

Upon entering the main building, you are greeted by the grand staircase, an iconic symbol of the Hotel New Grand. Take a moment to appreciate its beauty rather than hurrying to the second-floor lobby. Each side of the staircase features a fruit basket sculpture on each side, a nod to the welcome fruits commonly found in international hotels, symbolizing hospitality. The handrails are adorned with hand-fired Italian tiles, custom-made in various shapes, some curved, others diamond-shaped, each carefully placed and uniquely textured, contributing to the overall aesthetic with their beautiful bluish hues.

As you ascend the stairs and look up to the ceiling, you will see tapestries with scenes of oriental celestial maidens playing music, a surprise in this European-style hotel. The arches by the tapestries also feature Japanese-style motifs. The hanging lights, made of washi paper and designed after those found in Buddhist monasteries, also have Japanese flair.

Thus looking closely, you will come upon various Japanese and Eastern elements, each meticulously crafted. A great many foreign guests likely have felt the exotic charm of this place. The main building of the Hotel New Grand is thus infused with a welcoming spirit visible in its details.

a.天使の肘掛け

エキゾチックな魅力が旅情をかきたてる。

ホテルニューグランド本館を設計したのは、国立博物館や銀座の和光を手がけた渡辺仁。渡辺が大切にしたのは横浜の旅情を感じてもらうことで、その想いは本館2階ザ・ロビーに表現されている。

大階段を上がると、そこは約5mの天井高をもつスケールある空間。大きな窓が連なり、銀杏並木とその向こうにある海の碧を室内に呼び込んでいる。ここに座り、ぼんやりと窓外を眺めていると、時が止まり、旅路にある情緒に心が奪われる。自分がいま、横浜にいることの歓びが感じられる空間だ。

素晴らしいのは空間だけではない。 そこに置かれている家具は「横浜家具」という希少なもの。 その昔、横浜に住んでいた外国人が、自分たちが使っている洋家具の修理を横浜の家具職人に依頼した。そうするうちに家具職人たちは洋家具がもつ曲線や装飾の美しさを知り、 その造りなどをおぼえ、やがて自分たちで洋家具を造作するようになる。 それが「横浜家具」と呼ばれ、いまでは価値あるものになっている。

ここに置かれている家具のなかでも、ひときわ存在感を放っているのがキングスチェアと呼ばれるイス。その威風堂々としたデザインは、まさに王の風格。肘掛けには勝利の女神であるニケの装飾が施されていて、撫でると幸運が訪れるという噂も。製造された当時、高級車一台分ほどの価格がついていたというこのイスに、いまでは誰でも気軽に腰掛けることができる。

そしてこの空間にもまた、日本やアジアのテイストがちりばめられている。マホガニーの柱の上には弁財天を描いた燭台があり、壁面にはインドの聖典であるカーマスートラのレリーフ、天井から吊り下げられた照明には巴紋がある。和と洋が高い次元で調和し、ここを独特な空間に仕上げている。

海外からの旅行客は日本やアジアのテイストに心が躍り、 日本の旅行客はヨーロピアンな雰囲気にうっとりとする。 和洋折衷な設えで旅情をかきたて、旅人を上質にもてなす空間。 ホテルニューグランドには迎賓の心が息づいている。

Exotic charm that stirs the hearts of travelers.

The main building of the Hotel New Grand was designed by Jin Watanabe, known for his work on the National Museum and the Wako building in Ginza. Watanabe aimed to capture Yokohama’s spirit of travel, a theme that resonates throughout the second-floor lobby.

Ascending the grand staircase, you enter a spacious area with a ceiling height of about 5 meters, featuring large windows that overlook a ginkgo tree-lined avenue and the blue sea beyond. Here, time seems to pause, immersing visitors in the emotional depth of their journey. This is a space where one can truly savor the joy of being in Yokohama.

The splendor extends to the furniture, a rare kind known as “Yokohama furniture.” Historically, foreigners living in Yokohama had their Western furniture repaired by local craftsmen, who became acquainted with the beautiful curves and decorations of Western furniture, learned its construction, and eventually started making their own pieces. Yokohama furniture is now quite valuable.

Among the furniture, the chair known as the King’s Chair stands out with its regal presence and presence fit for royalty. Adorned with symbols of Nike, the goddess of victory, its armrests are rumored to bring good luck to those who touch them. Although the chair originally cost as much as a luxury car, now anyone can casually sit on it.

This space is also sprinkled with Japanese and Asian touches. The mahogany pillars are topped with candleholders depicting Benzaiten, the walls feature Kama Sutra reliefs, and the hanging lights bear the tomoe crest. The high level of harmony between the Japanese and Western elements makes this a unique space.

Travelers from abroad are thrilled by the Japanese and Asian elements, while Japanese visitors are drawn to the European ambiance. This eclectic mix of design elements ignites wanderlust and offers refined hospitality, embodying the Hotel New Grand’s welcoming spirit to all guests.

※画像は2名様分のイメージです

色鮮やかなティーフーズが夏の思い出を彩る

サマーアフタヌーンティー

2024年7月1日(月)~8月31日(土)

料金 ¥6,704(税込・サービス料込)

<土日祝はご利用時間を3時間とさせていただきます>

提供店舗 本館1階 ロビーラウンジ ラ・テラス

https://www.hotel-newgrand.co.jp/la-terrasse/

地球温暖化への思いが生む、空想の空間。

Feature | 2024.05.23

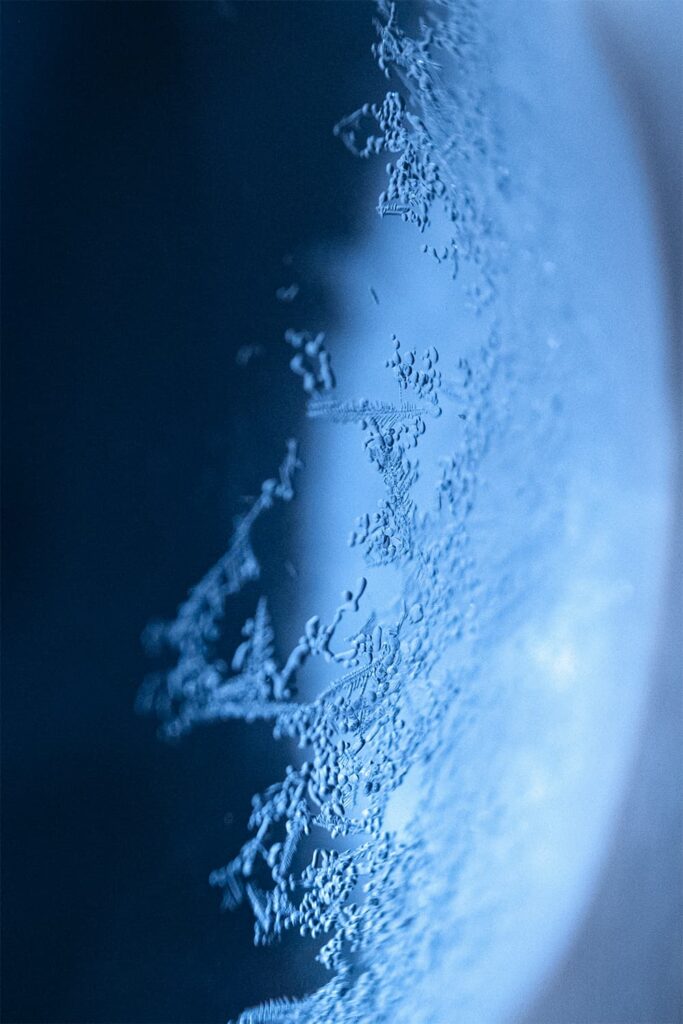

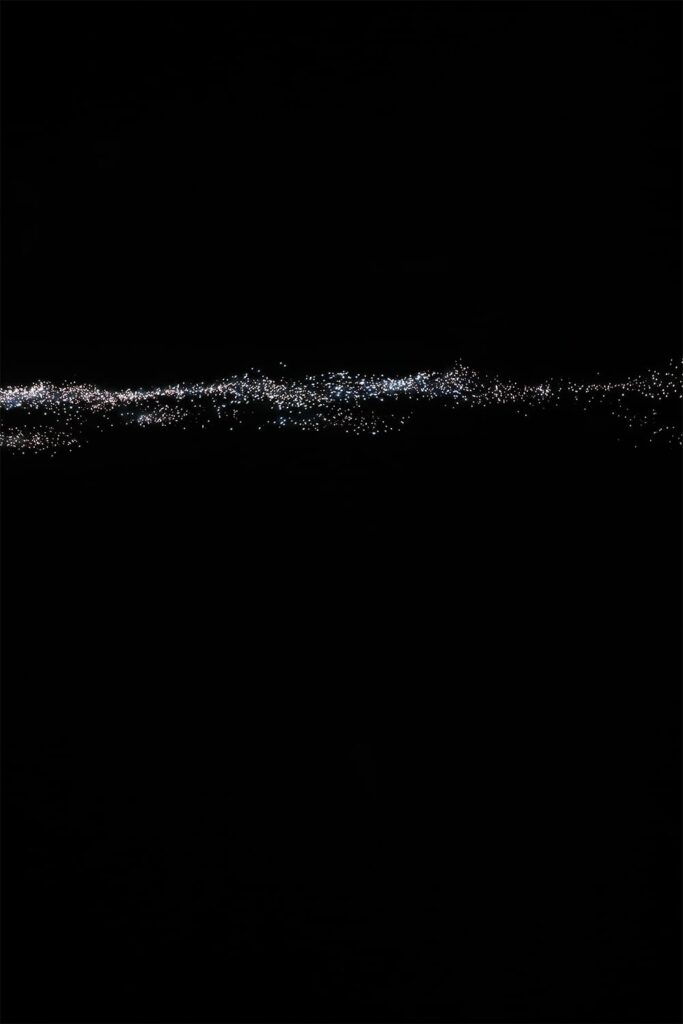

「もしも宇宙に雪が降ったら」。

そんなイメージを、実際の風景を連鎖させながら表現。ここにあるのに、どこにもない、「111l」の世界。

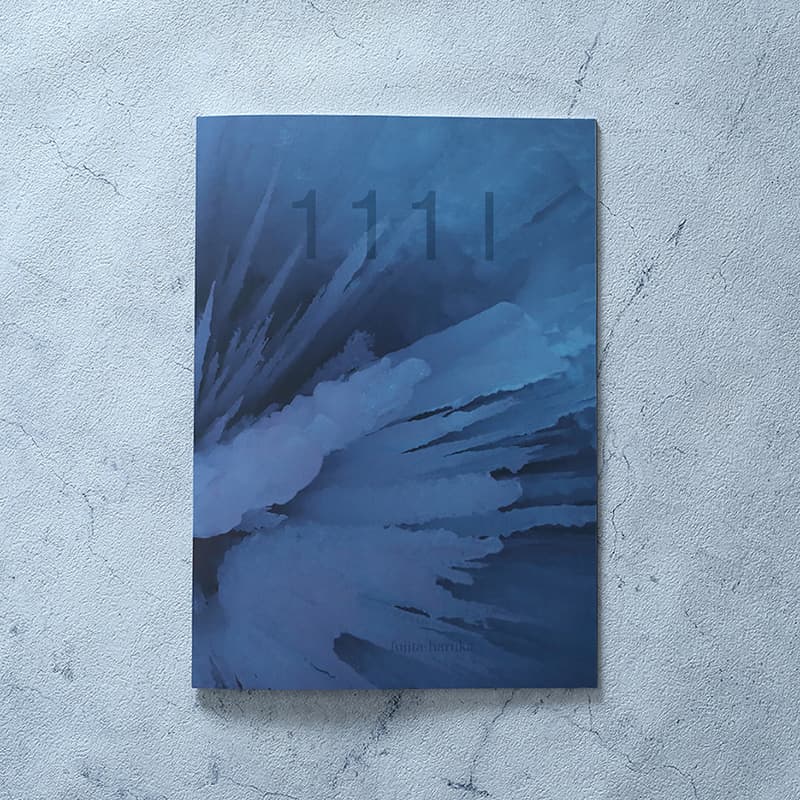

空間とは。辞書で引くと「物体が存在しないで空いている所。また、あらゆる方向への広がり」とある。実際にはない虚構の空間というものもあるし、近頃ではメタバースというインターネット上の仮想空間もある。そうして空間について思いを巡らせるきっかけになったのが写真家 藤田はるか氏の写真集を見たから。タイトルは「111l」。これは111という数字とlightの頭文字であるlからなる言葉で111光年を意味しているという。

これがなんとも不思議な写真集。現実にある風景を撮っているようだが、それが地球上のものとは思えない。ページをめくりながらイメージが連鎖し、壮大な世界をつくりだす。この写真集で表現されているのは「もしも宇宙に雪が降ったら」という空想の空間。

ある年のこと。いつもなら藤田氏の家の近所で8月に開催される花火大会が、気候変動のため10月開催へと変更された。同じ頃、中谷宇吉郎雪の科学館の館長から「宇宙のとある惑星の大気中に水蒸気の存在が確認された」と聞いた藤田氏。その話から“もしかしたら宇宙でも雪が降るかもしれない” という思いにとらわれ、温暖化が進み悪循環の渦にある地球の現状と交互に、頭の片隅で誰もいない暗い空間で舞う雪を想い描くようになる。そうしてそれを写真集として表現したのが「111l」。「いつか人類は、かつては美しかったこの土地を逃れて旅立つのだろうか。残された私たちは様々な思いと願いを載せて花火を打ち上げるかもしれない」と藤田氏は想像する。

豊かなイマジネーションのなかで、現実は空想となる。そんなアンビバレントな世界が「111l」で楽しめる。

A fantastical space born from concern about global warming.

What is space? According to the dictionary, it’s “a place empty of physical objects, extending in all directions.” Beyond tangible space, there are fictional realms and, more recently, virtual environments like the metaverse. My interest in space deepened after exploring Haruka Fujita’s photo book, 111l. Named for the number 111 and “l”, the initial of ‘light,’ the title means 111 light-years.

111l is a captivating photo book. It portrays seemingly real landscapes that possess an otherworldly quality. As one turns the pages, the images connect, conjuring a vast, expansive world. This book presents an imaginative realm, exploring the intriguing concept of snow falling in space. One year, the usual August fireworks festival near Fujita’s home was delayed until October due to climate change. Around the same time, he learned from the director of the Nakaya Ukichiro Museum of Snow and Ice that water vapor had been detected in the atmosphere of a distant planet. This sparked his imagination about the possibility of snow in space, juxtaposed with thoughts on Earth’s worsening climate crisis. These reflections inspired his photo book 111l. “Someday, humanity might flee this once beautiful land,” Fujita muses. “Those of us left behind might launch fireworks carrying our various thoughts and hopes.”

The artist’s rich imagination turns reality into fantasy, and 111l invites us to explore this ambivalent world.

『111l』

写真集『111 l』のオンライン展示が開催中。

ライトボックスによって浮かび出される藤田はるかの写真たち。

幻想的で、美しい世界が広がっています。

https://www.fujitaharukaphoto.com/111l-photo

写真集『111 l』展示会 開催

(入場料)無料

2024年 5月17日(金)〜6月3日(月)

月・金:13:00~18:00 / 土・日:12:00~17:00

※火・水・木(クローズ)

会場: MONO.LOGUES 東京都中野区中野5-30-16 メゾン小林101

https://www.monologues.jp/