年末の芸術風物詩はなぜ『第九』になったのか?

Essay|2024.12.20

Text _ Kotaro Sakata

今年は猛暑の夏が長く秋が短かった。早いもので、年末年始に向けての準備に追われ、慌ただしくなる季節となった。この季節はなにかと忙しいものであり、気が付くと忙しさにかまけて、自分の心のケアを怠っていることがある。そんな時期だからこそ、ゆっくり音楽でも聴きながら1年を振り返って来年への抱負を考えたりする時間を持ちたいものである。

しかし、こんな風に1年を振り返り、反省して、来年の準備をするのはまじめな日本人だけ?欧米では、一般にはキリスト生誕のクリスマスがメインの風物詩であり、ミサ曲などの宗教曲が流れる。つまり、年末の風物詩はクリスマスとなるわけだ。

しかし、日本では、クリスマスは『商戦的』なイベントとしてとらえられている傾向にあり、年越しに重点が置かれている。その一番の風物詩の一つがベートーヴェン最後の交響曲第9番 ニ短調 作品125。通称『第九』である。では、なぜこの曲が、日本で年末の風物詩になったのであろう。

諸説あるが、第二次世界大戦後の1940年代後半、どのイベントも客が集まらず、オーケストラ演奏も御多分に漏れず収入が少なく、年末年始の収入に困る状態であった。合唱付きで、演奏者も多く、ラジオ放送の普及や、ラジオでの『第九』人気にもあやかり、『客入りがいい曲目』であった『第九』を日本交響楽団(現在のNHK交響楽団)が演奏するようになり、それが全国の風物詩となったというのがどうやらファイナルアンサーである。

この70分を超える、全4楽章からなり、最終楽章には、合唱付きとなる大所帯で長大なシンフォニーは、ベートーヴェン以降にマーラーなどのお手本となる。3楽章までは、器楽のみで演奏され、それまで、演奏されて来たモチーフを、4楽章のバリトンの第一声 “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!” (「おお友よ、このような音ではない!」)と歌うことで、1~3楽章を全否定し、その後、これでもない。それでもない。と経て、『歓喜の歌』へと昇華していくのである。

歌詞は、フリードリヒ・フォン・シラーがフリーメイソンリーの理念を書いた詩作品『自由賛歌』を元に詩を書き直した『歓喜に寄す』としたところ、これをベートーヴェンが歌詞として1822年から1824年に書き直したものである。

この曲の最後は、 Über Sternen muß er wohnen. (「星々の上に、神は必ず住みたもう」)と、やはり宗教的要素であるところをあまり意識せずに、日本風に解釈してもよいのではないだろうか?つまり、この曲の持つ、『みんなで、集まって、幸多かれ!』と解釈するのが日本風なのだろう。

Why is Beethoven’s Ninth a year-end tradition in Japan?

This year saw a long, scorching summer and a fleeting autumn. As the busy year-end season approaches, many find themselves overwhelmed with preparations, often neglecting self-care in the process. What better time than now to pause, reflect on the past year, and set intentions for the next—all while enjoying some music? But is this reflective tradition uniquely Japanese? In Western countries, the year-end season revolves around Christmas, a celebration of Christ’s birth, accompanied by religious music like masses. Christmas is the defining tradition there. In Japan, however, Christmas tends to be viewed as a commercial event, with the focus instead on New Year’s celebrations. Among these, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Op. 125, famously known as the “Ninth,” has become a symbol of the season. Why this piece? The answer lies in post-World War II Japan during the late 1940s, when orchestras struggled to attract audiences, particularly at year-end. The Japan Symphony Orchestra (now the NHK Symphony Orchestra) capitalized on the symphony’s widespread popularity through radio broadcasts, offering the Ninth as a crowd-pleaser. Over time, it became a nationwide tradition.

Over 70 minutes long, this large-scale symphony, which has four movements, the last of which is the chorale finale, was a model for subsequent composers such as Mahler. The first three movements are instrumental pieces, and the motif played up to that point is completely denied by the baritone’s opening in the fourth movement, “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!” (“Oh friends, not these sounds!”), paving the way for “Ode to Joy.” The lyrics were adapted from Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy,” which was based on the ideas of Freemasonry, by Beethoven between 1822 and 1824.

The final line of the Ode, “Über Sternen muß er wohnen” (“Above the stars, God surely dwells”), has a religious element, but this aspect is downplayed in Japan, where the Ode’s is perhaps uniquely interpreted as a message to get together and be happy.

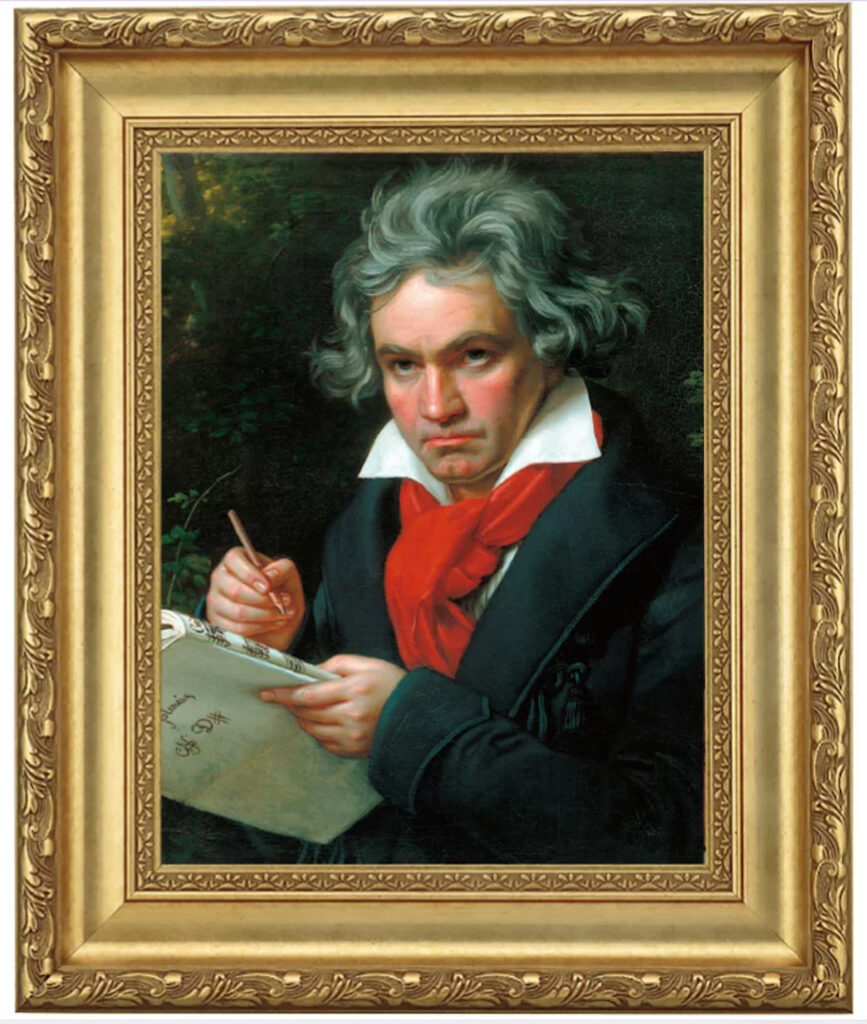

ベートーヴェンの肖像として最も有名なこの絵は、ドイツの画家ヨーゼフ・カール・シュティーラー(1781~1858)。手にはその頃作曲中だった〈ミサ・ソレムニス〉の楽譜が描かれています。

ベートーヴェンの補聴器:

ベートーヴェンが自ら指揮をした『第九』演奏会の時には、完全に聴力を失っており、演奏が終わって受けた観客の喝采も分からなかったという。

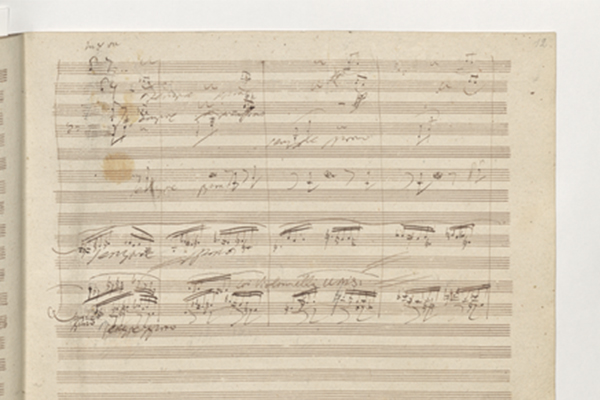

ベートーヴェン『第九』直筆譜